- News

- Reviews

- Bikes

- Components

- Bar tape & grips

- Bottom brackets

- Brake & gear cables

- Brake & STI levers

- Brake pads & spares

- Brakes

- Cassettes & freewheels

- Chains

- Chainsets & chainrings

- Derailleurs - front

- Derailleurs - rear

- Forks

- Gear levers & shifters

- Groupsets

- Handlebars & extensions

- Headsets

- Hubs

- Inner tubes

- Pedals

- Quick releases & skewers

- Saddles

- Seatposts

- Stems

- Wheels

- Tyres

- Tubeless valves

- Accessories

- Accessories - misc

- Computer mounts

- Bags

- Bar ends

- Bike bags & cases

- Bottle cages

- Bottles

- Cameras

- Car racks

- Child seats

- Computers

- Glasses

- GPS units

- Helmets

- Lights - front

- Lights - rear

- Lights - sets

- Locks

- Mirrors

- Mudguards

- Racks

- Pumps & CO2 inflators

- Puncture kits

- Reflectives

- Smart watches

- Stands and racks

- Trailers

- Clothing

- Health, fitness and nutrition

- Tools and workshop

- Miscellaneous

- Buyers Guides

- Features

- Forum

- Recommends

- Podcast

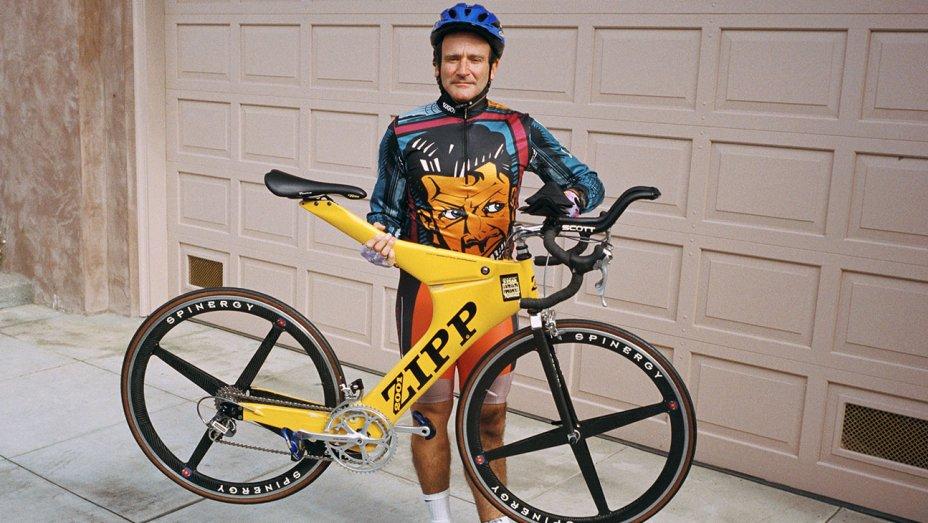

Giant MCR - image credit Tirivanhu Dzivakwi

Giant MCR - image credit Tirivanhu DzivakwiRemembering the Giant MCR, one of the first truly aero road bikes that ripped up the UCI rule book

Road bikes have changed a huge amount in the last couple of decades; but looking back at this classic Giant MCR from 1997, arguably one of the first truly aero road bikes, reminds us just what an exciting period the 1990s was for bike development, when the rules weren’t to be followed, but truly bent and broken.

Back in 2019, at the start of a road.cc rideout outside our office in Bath, our senior tech writer at the time David Arthur spotted someone rock up on one of these rare beasts. It certainly got everyone talking, and despite much talk of twitchiness when trying to handle the huge slab of carbon monocoque between your legs, it still appeared to be doing the owner proud.

A bit of history: the Giant MCR was released a few years after the stunning Lotus Sport 108, which Chris Boardman famously rode to Olympic victory in 1992. Both were designed by the late, great bicycle engineer Mike Burrows, and both tore up the conventional bicycle design book of the time.

A road-going version of the Lotus, the Lotus Sport 110, followed the track bike with provision for gears and brakes, and it’s this bike that the Giant-branded MCR is based on. Burrows worked for Giant in the 90s, helping to develop the company’s TCR compact frame design, revolutionising the modern road bike in the process.

Unfortunately, the radical design and the speed of the Lotus shocked the UCI so much that it brought in new technical rules that outlawed the design, ensuring that all bikes developed since retain the classic double diamond appearance of a road bike. In 1996 - and unfortunately for Giant, just before the release of the MCR - the UCI unleashed Principle 1.3 on the world to set this in stone, ensuring future bikes of the peloton remained roughly in double diamond form.

In the UCI's latest clarification guide of its technical regulations, it summarises the principle like this: "The UCI Regulations assert the primacy of man over machine. Observance of the regulations by all parties involved facilitates sporting fairness and safety during competition."

Anyway... the MCR frame is a full carbon fibre monocoque with matching carbon fork, with (mostly) internal cable routing, an aero seatpost and a single water bottle mount.

While it does look rather similar to the Lotus bike, the single-leg fork and single chainstay were replaced with more conventional parts so a groupset and brakes could be fitted for riding on the road.

Giant produced the MCR for just four years, beginning in 1997 with a top-tier MCR 1 and second-tier MCR 2. The MCR1 was black and purple, so the one we saw four years ago was an MCR 2 that came with a 9-speed Ultegra groupset.

It’s a heavy bike by today’s standards, with a claimed 9.9kg complete weight when specced with the Ultegra groupset and carbon spoked wheels, also designed by Mike Burrows. It cost £2,000 in 1997, which would be around £3,748 in today's money - a relative bargain compared to the road superbikes of today.

There isn't a huge amount of information out there on the Giant MCR, but there is an owner's club on Facebook, and we managed to speak briefly with one of those proud owners. Tirivanhu Dzivakwi (above) had this to say about his MCR that he rides regularly around the backroads of Harare:

"I got the frame and fork from a friend in 2021 and had to rebuild it.

"This bike is stable and fast compared to my Raleigh Microsoft Carbon. The moment I started using this bike my average speed increased tremendously. I used to average 21 to 24km/h, but with this one I twice managed to hit an average of 31km/h.

"I haven't tried it with finer wheelsets and am confident it's a superbike. With a good groupset it will be a bullet."

A happy MCR owner indeed!

So, why the explosion of unconventional frames in the 90s anyway? Essentially it was born out of the increased use of carbon fibre by bike designers. When Greg LeMond proved the value of aerodynamics in 1989, carbon was in its infancy, but bike designers saw huge potential to create frame shapes previously impossible with metal. Carbon enabled greater freedom to produce aerodynamically superior frames that reduced drag and increased the speed a cyclist could ride at.

Thanks to the pesky UCI, arguably nothing too radical has happened in the world of road and time trial bike design beyond cables disappearing, weights dropping and disc brakes appearing (thus weights going back up again) since the late 90s - but the increased popularity and investment into the UCI-free sport of triathlon has led to a glut of radical and unconventional frames since the mid-2010s, such as the "mind-bending" Cervelo P5X, Diamondback's MotoGP-inspired Andean and the bike in the picture above, the Cadex Tri.

The Cadex Tri was used with great success by Kristian Blummenfelt to win the Ironman World Championships in 2022, and you can clearly see the silhouette of the frame is quite similar to the MCR. Is this solid evidence that the MCR's frame shape truly was faster than any double diamond aero road frame being manufactured today? If like the UCI you believe in man (or woman) over machine, maybe the ban wasn't such a bad idea after all...

Jack has been writing about cycling and multisport for over a decade, arriving at road.cc via 220 Triathlon Magazine in 2017. He worked across all areas of the website including tech, news and video, and also contributed to eBikeTips before being named Editor of road.cc in 2021 (much to his surprise). Jack has been hooked on cycling since his student days, and currently has a Trek 1.2 for winter riding, a beloved Bickerton folding bike for getting around town and an extra beloved custom Ridley Helium SLX for fantasising about going fast in his stable. Jack has never won a bike race, but does have a master's degree in print journalism and two Guinness World Records for pogo sticking (it's a long story).

Latest Comments

- Pink Duck 14 min 45 sec ago

The Cyclists Dismount signage is now up, not that anyone pays any attention to it.

- Pub bike 19 min 25 sec ago

Needless to say (but here goes anyway) the bollards get dirty because motorists crash into them, which further justifies having them there because...

- Pub bike 22 min 18 sec ago

It would seem to be 'relative power' only when the weight is taken into consideration otherwise it would be called 'absolute power' or some such...

- hawkinspeter 30 min 18 sec ago

I think it's just a handful of cars that use Lidar currently, but it'll likely become the norm for autonomous vehicles as it has distinct...

- PRSboy 49 min 27 sec ago

Ah-ha, thank you... Will put you back on my short-list!

- j4m1eb 1 hour 17 min ago

Call me a cynic but Trek and Specialized have "one bike to rule them all" becuase it's better for profitability. Less SKUs and less manufacturing...

- the little onion 1 hour 29 min ago

it is absolutely transparently NOT about the trees

- Rendel Harris 2 hours 40 min ago

I don't think he's having a dig at the French teams, he just means that Paris-Nice is a massively prestigious race in France (probably second only...

- chrisonabike 2 hours 46 min ago

Too small ... haven't read the exact CROW specs but normally the UK errs in the other direction, applying a bit of paint to a large roundabout...

Add new comment

3 comments

That is truly fugly.

Andy Wilkinson was using an MCR when he set a batch of time-trialling competition records in the mid to late 90s.

With just one awkwardly located bottle location, it makes more sense as a TT bike. However the seat tube angle is more roadbike appropriate, so needs slamming a TT saddle all the way forward.

Never noticed mine being twitchy - having raced IM Nice, Wimbleball & standard dist at Bournemouth this month etc.

Note: unlike the CADEX frame, the MCR doesn't need seatstays, and the chainstays fair the cassette & non-driveside rear axle (limiting disc wheel & cassette size options).