- News

- Reviews

- Bikes

- Accessories

- Accessories - misc

- Computer mounts

- Bags

- Bar ends

- Bike bags & cases

- Bottle cages

- Bottles

- Cameras

- Car racks

- Child seats

- Computers

- Glasses

- GPS units

- Helmets

- Lights - front

- Lights - rear

- Lights - sets

- Locks

- Mirrors

- Mudguards

- Racks

- Pumps & CO2 inflators

- Puncture kits

- Reflectives

- Smart watches

- Stands and racks

- Trailers

- Clothing

- Components

- Bar tape & grips

- Bottom brackets

- Brake & gear cables

- Brake & STI levers

- Brake pads & spares

- Brakes

- Cassettes & freewheels

- Chains

- Chainsets & chainrings

- Derailleurs - front

- Derailleurs - rear

- Forks

- Gear levers & shifters

- Groupsets

- Handlebars & extensions

- Headsets

- Hubs

- Inner tubes

- Pedals

- Quick releases & skewers

- Saddles

- Seatposts

- Stems

- Wheels

- Tyres

- Health, fitness and nutrition

- Tools and workshop

- Miscellaneous

- Tubeless valves

- Buyers Guides

- Features

- Forum

- Recommends

- Podcast

feature

road.cc Podcast episode 49

road.cc Podcast episode 49How to save a bike race: Rás Tailteann organiser on keeping Ireland’s biggest race alive, ‘difficult second album syndrome’, and why some races just mean more

In just under a month’s time, on Wednesday 17 May, the 68th edition of the Rás Tailteann, Ireland’s most historic and celebrated bicycle race, and one of the country’s most iconic sporting events, will set off from Navan, Co. Meath for five days of tough, hilly, and frenetic racing.

However, despite the jubilant and festival-like scenes which will greet the peloton as it snakes its way towards the seaside town of Blackrock, the Rás – known in Irish cycling circles simply as the Big One – has endured a turbulent last few years.

Listen to the road.cc Podcast on Apple Podcasts

Listen to the road.cc Podcast on Spotify

Listen to the road.cc Podcast on Amazon Music

*Press play to listen to the interview, or scroll on for a bonus feature on the Rás and the fight to keep it alive

In 2019, after several lean years when the purse strings were tightened thanks to the withdrawal of the event’s title sponsor, the week-long race was cancelled for the first time since its establishment in 1953. Then, like bike races all over the world, the Rás fell victim to the Covid-19 pandemic, which saw the next two editions shelved.

After four long, difficult years off the road, it eventually returned in June last year – in a new, condensed five-day format and with a decidedly more homespun feel, compared to the international affair it had become in the 21st century, as local Irish riders dominated for the first time in a generation.

The resurrected race was also welcomed back with open arms by throngs of enthusiastic roadside supporters and positive press coverage, and the stages themselves featured some thrillingly attacking racing to boot.

But while the glorious sunshine that greeted the final stage of the Rás in Blackrock last year reflected the mood of the riders, organisers, and spectators, basking in a job well done, dark clouds have continued to linger over the race’s precarious future.

Like other international stage races such as the Women’s Tour in Britain, the 2023 edition of which was put on ice last month after an aborted crowdfunding attempt, the Rás has suffered from funding issues, rising costs, and the lack of a stable title sponsor.

In January, race director Gerard Campbell, the man charged last year with resuscitating the Rás, claimed that he was only “90 percent sure” that the 2023 edition would even go ahead. And last month Campbell argued that the event’s financial position – currently reliant on short-term sponsorship deals – is “unsustainable”.

In a wide-ranging interview with the road.cc Podcast (available to listen to above) which touches on everything from the logistical problems associated with running a major bike race to the sense of communal pride instilled by the Rás, Campbell – whose association with the race he now organises stretches back almost 50 years – strikes a cautiously optimistic tone about his race’s future (though as he notes during our chat, the Rás “doesn’t belong to anybody. It belongs to the sport”).

Reflecting on a race intrinsically linked to both himself and wider Irish sporting culture, the long-serving Drogheda Wheelers secretary also explains how he and his team have managed to keep the show (literally) on the road during the past two years and why, after months of stress and hundreds of phone calls, finally being on the race itself can feel like a holiday.

Oh, and why we shouldn’t expect to see him in the lead car of a WorldTour race anytime soon…

A fifty-year love affair

Ger Campbell is a busy man.

Immediately after our conversation ends, on a weekday evening less than two months before the opening stage of the Rás Tailteann in Navan, the 62-year-old is straight onto yet another Zoom call.

“I’m looking forward to the 21st of May, at around 7pm, to be honest,” he laughs when I ask him if he’s excited about this year’s race, the second of his tenure as race director.

“Every day is bringing a new issue, a new problem, but it’s no different from any other year really. It’s just logistical stuff, and problems that crop up on a daily basis. But we’re getting there.”

Campbell with race winner Daire Feeley after the final stage of the 2022 Rás in Blackrock

“We’re getting there” appears to be the mantra of the Rás’s organising team. Campbell’s 2023 has been a seemingly endless chain of phone calls and meetings, sourcing and finalising accommodation for the race’s 500-strong travelling family, liaising with the police over security preparations and the placement of finish lines (one proposed finish is already onto Plan D, Campbell tells me), and making arrangements with interested teams from the UK, Europe, and beyond.

It’s a tough and unrelenting gig for someone who, by his own admission, stumbled into the role “by accident” following the departure of former race director Eugene Moriarty in early 2022.

Not that Campbell’s almost lifelong relationship with the Rás is accidental, of course.

His first taste of the race, as well as cycle racing in general, came as a ten-year-old, in 1971, when fellow Meath native Colm Nulty won a stage and the general classification of an event known throughout Ireland as the Big One.

“I knew nothing about cycling, I knew nothing about the Rás, but at the time that was a huge thing in the locality, absolutely huge,” Campbell says.

After heading to Dundalk to watch the finish of the following year’s opening stage, he was well and truly bitten by the cycling bug, and started racing with a group of friends.

In 1978, the same year he took part in the inaugural Junior Tour of Ireland alongside future pros Martin Earley and Sean Yates, a seventeen-year-old Campbell was invited along to the Rás as a rather green mechanic.

“That was the start of a real love affair with the race,” he says.

1978’s brief and nervy stint servicing bikes marked the start of a 40-year unbroken association with the Rás. Between 1979 – the year Stephen Roche took the overall win, less than two years before the Dundrum man burst onto the pro scene by winning Paris-Nice – and 1982 he swapped the race car for the peloton, cementing his status as a ‘man of the Rás’ (the name given to those hardy souls, like the Tour de France’s Giants of the Road, brave enough to withstand the gruelling week of racing).

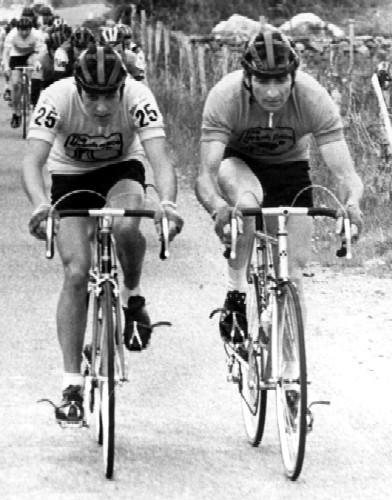

A young Stephen Roche takes on former winner Colm Nulty at the 1979 Rás Tailteann (credit: Rás Tailteann)

He then took on a series of different roles, including working with teams, providing neutral service, the “illustrious” role of route marking, and then designing the route, before eventually taking over as race director in January 2022, in the midst of the race’s four-year financial and Covid-induced hiatus, after former organiser Moriarty emigrated to Amsterdam.

It’s perhaps fitting then, that the task of reviving the race fell to someone so steeped in its folklore. And there are very few bike races with as much history (and a complicated history at that) and tradition as the Rás Tailteann.

In a similar vein to some of its perhaps more illustrious counterparts on the continent, the Rás is much more than a simple bike race. In fact, like the Tour of Flanders, the race is intrinsically linked to Ireland’s complex sporting, cultural, and political identities.

The Rás – the very name of which deliberately links it to Ireland’s medieval Tailteann Games, a kind of Gaelic Olympics, the revival of which became a cultural focal point for Irish nationalists in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century – in its early days fostered the all-island, inter-county competition and communal and national pride which remains a key feature of Gaelic games such as football and hurling, the country’s national sports. Spectators flocked to the roadsides to cheer on their local hero, battling it out against the best Ireland had to offer.

Founded in 1953, the race also proved a symbol for Ireland’s sporting and political divisions at the time. Its founder Joe Christle was an IRA man, who used his event to call for an end to the partition of the island, with stages of the inaugural edition even paying homage to the 1798 and 1916 rebellions against British rule.

Along with the National Cycling Association, a governing body with anti-partitionist, republican leanings which saw it outlawed by the UCI and IOC, Christle controversially brought the race across the border on several occasions in the late 1950s – at a time when the IRA was carrying out a guerrilla campaign in Northern Ireland – prompting clashes with the police and some unsavoury scenes.

The Rás bunch triumphantly waves an Irish tricolour “recaptured” from the RUC during a 1956 visit by the race to Northern Ireland (credit: Rás Tailteann)

As well as its broader political and societal implications, the Rás also stood as a marker of the internal conflict within Irish cycling itself, which by the 1950s was divided into three different governing bodies and embroiled in a bitter power struggle based on Ireland’s political divisions. Those divisions even manifested in the creation of two rival national tours in Ireland – the Rás and the Tour of Ireland, organised by the UCI-recognised and border-adhering governing body, the CRE.

By the late 1970s, the frosty relations which had defined post-partition Irish cycling had finally thawed – with Campbell’s debut, fittingly, coming in the first truly ‘open’ Rás in 1979 – and the eight-day stage race eventually developed into a big, international affair. By the race’s hiatus in 2019, it boasted a seriously impressive list of overall and stage winners, from home heroes Roche and Sam Bennett to the likes of Tony Martin, John Degenkolb, Simon Yates, and Jai Hindley.

But, while the race grew in stature and importance at the turn of the 21st century, Campbell insists that the beauty of the Rás still stems from the local communities it passes through.

“When we took over the running of the race, it was important that it was the Rás,” he says. “We could have come back from a four-year hiatus, and called it anything, but we wouldn’t have had the kids out on the side of the road with their paper flags, because to them the Rás was passing their gate. It wasn’t some new thing, it was the Rás, steeped in history.

“There are some places in the country where it’s more important, and holds a more special place than it does in other parts, but generally in terms of Irish sporting culture, it has huge traditions.

“I’ll give you one example. The first Rás I went to, 1978, there was a stage that year from Galway city to Clifden. That particular day there were fishermen lost at sea off the coast of Roundstone, Co Galway. The race was asked to pass through Roundstone with a little bit of dignity, no noise, no blowing horns. And it did, and when we got to Clifden that night, the news had spread that the fishermen had been found safe, which was great.

“It was ten years later before we went through Roundstone again, in 1988. There was an intermediate sprint in Roundstone, and as route markers we were putting down the preparations outside this hotel. The woman who owned the hotel came out and said, ‘Ah the Rás is back. We couldn’t welcome you the last time ten years ago, come in and have a drink’. And that’s the truth.”

“It is absolutely unsustainable to do this going forward”

However, despite the race’s unique role in Irish sporting life, it has not been spared from the financial turmoil gripping bike races in recent years.

In 2017 title sponsor An Post – a longstanding supporter of Irish cycling which took over in 2011 after almost thirty years of sponsorship by FBD Insurance – pulled out. Though careful budgeting, using the race’s cash reserves, allowed the event to go ahead the following year, the organisers’ futile search for a sponsor saw the Rás cancelled for the first time in its then 66-year history in 2019.

A new, shorter format, down to five days from the traditional eight and without the UCI status or ranking points that attracted an international field of third-tier teams and future stars, was planned for the race’s resurrection in 2020, but then, of course, the pandemic got in the way.

Under Campbell’s stewardship, the race staged a successful return last June, albeit with a more homespun, almost parochial feel – four out of the five stages were won by Irish riders, while yellow jersey winner Daire Feeley was the first man from Ireland to take the GC since Stephen Gallagher in 2008, and the first one to do so representing a county since Armagh’s Tommy Evans back in 1996.

While some onlookers have bemoaned the loss of three stages and the race’s international standing, Campbell reckons the stripped back approach is key to ensuring the event’s long-term survival.

“My argument, even during the An Post years, when we had [third-tier professional] Conti teams coming over, has always been that if a Frenchman wins the stage, that’s all that matters to the ordinary sports supporter at the side of the road. ‘Oh, a fella from France won’. It doesn’t matter if he’s a Conti rider, he’s a visitor from France. And it was important to me to still do that, but also reducing the costs by not bringing in the Conti teams.

“The special history and culture that’s around the race preceded any pro teams coming in. The essence and heart of the first thirty years was solely the county rider. And I suppose, last year we went backways – but by doing that, with four of the five stages being won by Irish riders, and the race being won by an Irish rider, that created far more buzz than if there were any Conti teams.

“The coverage and feedback we got last year, because we went back to its roots – and of course, you’re going to get some negative comments, but it was 90 percent positive – people said it was back where it belongs, Irish riders can compete again.”

Reflecting on what it meant to orchestrate the successful return of a race that means so much to him, Campbell said: “If a WorldTour race came to Ireland tomorrow – and I wouldn’t be asked, don’t get me wrong, I don’t hold that high a status – and someone asked me to be the race director, I would have absolutely zilch interest in taking on that job.

“I did it because it was the Rás, no other reason. As we approached the circuit in Blackrock [on the final stage of the 2022 race], I welled up so much that I told my son to keep driving for another lap, as I couldn’t get out of the car. And even when I did get out, I was so emotional – look at the crowds that have come to see us, we’ve been away four years, we’ve done something right.”

However, while Campbell believes the necessary changes that were made to the race, including shortening it to five days (an experiment that will, due to budget constraints, continue in 2023), were universally welcomed by riders and fans alike, doubts have continued to linger over the race’s future this year.

Campbell says that the Rás entered 2023 with a £60,000 funding gap, with careful budgeting – aided by the race’s move back to May from last year’s June slot, which has significantly reduced accommodation costs – and the successful persuasion of one of the current jersey sponsors to increase their input on a “one-off” basis, as well as some last-minute additional funding from Sport Ireland and, just this week, Cycling Ireland, has ensured that the race can go ahead, “just about”, as Campbell notes.

But the organiser insists that the piecemeal, short-term nature of the race’s current funding structure is “unsustainable”, and that lessons have already been learned from last year’s comeback edition, including the need to adopt a longer-term perspective, beyond just the event coming up quickly on the horizon.

“It is absolutely unsustainable to do this going forward,” he says. “We spent the six weeks after Christmas begging for money, when I should have been focusing on the nuts and bolts of the race.”

The sponsorship woes and rising costs impacting Campbell and the Rás’s organising team have also been felt elsewhere lately. Last month, the UK-based Women’s Tour, one of the biggest women’s stage races in the world, cancelled its 2023 edition citing the effects of inflation and the lack of a title sponsor on its current funding crisis. Meanwhile, in Ireland, another stage race, the Tour of Ulster, was called off for the second year running.

Campbell believes that, despite the widespread and positive coverage received by the Rás last year in the national press, major sponsors are unwilling to invest in the race thanks to the magnetic pull of Gaelic games and Irish rugby, which already attract the same rural, nationwide market – and therefore customers for potential sponsors – that the Rás relies upon for its roadside support.

“This year has been a bit, like they say in the music industry, ‘difficult second album syndrome’. We got something for nothing off someone last year, maybe they won’t give it to us for nothing this year,” he says.

“But, look, it’s testament to the lads in the organising group, who have begged to get money. But this can’t go on forever. Driving home from the race last year, I thought sponsorship was going to fall out of the sky – I was totally naïve. But you learn from your mistakes, and we’re already looking towards 2024.”

Despite his ongoing concerns over the stability of the race’s future, Campbell is nevertheless confident that his team can repeat the success of 2022 next month.

“If you do your job properly in the weeks and months leading up to the race, as soon as the flag drops on day one, you’re on a holiday. Now, that’s not necessarily true, but you know what I’m saying,” he laughs.

“It works because there are 100 people, all able to do their one percent, and one we get out of town on day one, it all seamlessly falls into place. Okay, you’re going to have issues and problems along the way, but the main part of it falls seamlessly into place.”

So, what does Campbell predict for the future of a race that has defined his own sporting life, as well as that of his country?

“I’d love it to be financially stable. I’d love to see it going in the vein it’s going at the moment, whether that would be acceptable to everyone, who knows.

“The Rás Tailteann doesn’t belong to anybody. It belongs to the sport in Ireland. So, it’s unique in that way. I’m doing this for the love of the event and I hope that someone will do it after me, for the love of the event.

“The hope that it will continue is hugely important to me. I’d have thrown my head up at this months ago, only it’s the Rás. If it was any other event, I’d have thrown my head up at it.”

The road.cc Podcast is available on Apple Podcasts, Spotify and Amazon Music, and if you have an Alexa you can just tell it to play the road.cc Podcast. It's also embedded further up the page, so you can just press play.

At the time of broadcast, our listeners can also get a free Heart-Rate Monitor with the purchase of a Hammerhead Karoo 2. Visit hammerhead.io right now and use promo code ROADCC at checkout to get yours.

After obtaining a PhD, lecturing, and hosting a history podcast at Queen’s University Belfast, Ryan joined road.cc in December 2021 and since then has kept the site’s readers and listeners informed and enthralled (well at least occasionally) on news, the live blog, and the road.cc Podcast. After boarding a wrong bus at the world championships and ruining a good pair of jeans at the cyclocross, he now serves as road.cc’s senior news writer. Before his foray into cycling journalism, he wallowed in the equally pitiless world of academia, where he wrote a book about Victorian politics and droned on about cycling and bikes to classes of bored students (while taking every chance he could get to talk about cycling in print or on the radio). He can be found riding his bike very slowly around the narrow, scenic country lanes of Co. Down.

While I agree with the sentiment, there doesn't always need to be a 20mph sign (for the very reason that it is the new default). I will confess to...

Oldfield Lane, Altrincham, which links Oldfield Brow to Dunham Park was permanently closed to motor traffic during the pandemic....

Very sad news this, I rode with this lad once on a new group ride I was trying out last year. He was very welcoming and I could tell he was a kind...

Agreed, and I'd contribute....

Thanks for your thoughts David. Argos is looking a good bet.

I'm pretty sure this is at least the third time the BBC have had a story on this - not sure why they keep forgetting that they've covered it.

Watching sports seems super boring to me, so not a problem....

Wattbike are notorious for releasing products before the software is ready. Likely long term it will be fine....

That is a horror show. A gravel racers bike but since it has a motor no racer can use it....

Have you seen the prices for vinyl records these days? Music piracy is still alive and kicking.