- News

- Reviews

- Bikes

- Accessories

- Accessories - misc

- Computer mounts

- Bags

- Bar ends

- Bike bags & cases

- Bottle cages

- Bottles

- Cameras

- Car racks

- Child seats

- Computers

- Glasses

- GPS units

- Helmets

- Lights - front

- Lights - rear

- Lights - sets

- Locks

- Mirrors

- Mudguards

- Racks

- Pumps & CO2 inflators

- Puncture kits

- Reflectives

- Smart watches

- Stands and racks

- Trailers

- Clothing

- Components

- Bar tape & grips

- Bottom brackets

- Brake & gear cables

- Brake & STI levers

- Brake pads & spares

- Brakes

- Cassettes & freewheels

- Chains

- Chainsets & chainrings

- Derailleurs - front

- Derailleurs - rear

- Forks

- Gear levers & shifters

- Groupsets

- Handlebars & extensions

- Headsets

- Hubs

- Inner tubes

- Pedals

- Quick releases & skewers

- Saddles

- Seatposts

- Stems

- Wheels

- Tyres

- Health, fitness and nutrition

- Tools and workshop

- Miscellaneous

- Tubeless valves

- Buyers Guides

- Features

- Forum

- Recommends

- Podcast

feature

Italy's Tour de France winners

Italy's Tour de France winnersRenaissance riders: Italy’s Tour de France winners, from Coppi and Bartali to Pantani and Nibali

France, and its politics, society, and culture, has long been inspired and influenced by its neighbours in Italy. In the 16th century, aided by the conquests of Louis XII and Francis I’s armies into Lombardy, the Renaissance – that great cultural movement towards modernity – took hold in France.

Though not entirely supplanting the country’s old gothic style, French aristocrats, besotted with the prestige attached to the new style, soon began importing the best Italian architects and artists. Leonardo da Vinci, Rosso Fiorentino, and Benvenuto Cellini were active at Francis I’s court, their influence most strikingly evident at the Château de Fontainebleau, an early exemplar of Mannerism.

Since then, some of Paris’ most famous landmarks, such as the Arc de Triomphe, the Palace of Versailles, and the Panthéon were inspired by Italian architecture, while the ideological and political heft of the Renaissance laid the groundwork for the Enlightenment and later French Revolution.

From the turn of the 20th century, however, it could be argued that some of Italy’s most influential figures across the Alps have been its cyclists.

From the groundbreaking exploits of Ottavio Bottechia and the era-defining talents and mythology of Fausto Coppi and Gino Bartali, to the triumph and tragedy of Marco Pantani and the swashbuckling style of Vincenzo Nibali, Italy’s cyclists have long stamped an indelible mark on the Tour de France, one of the bastions of French sporting culture and life.

(A.S.O./Jonathan Biche)

So, it may be a surprise to learn that – despite the Tour frequently nipping into Italy for a stage or two, and the reverence felt towards bike racing and the Giro d’Italia – the 2024 edition is the first in the race’s 121-year history to get underway in the Bel Paese.

To paraphrase the Giro’s overused marketing slogan of recent years, the world’s most important race is starting in the most beautiful place.

And like most recent Tour starts, as well as taking in the host country’s geography, architecture, cuisine, and culture, Italy’s maiden Tour de France Grand Départ will also pay homage to those riders who have defined the sport in both countries.

Along with marking the 100th anniversary of Bottechia and Italy’s first win at the Tour, the first stage sees the peloton set off from the Tuscan capital of Florence, the home of 1938 and 1948 winner Bartali, before a rugged trek through the Apennines – the training ground for so many Italian champions – takes them to Rimini, where Marco Pantani died in such grim, tragic circumstances 20 years ago.

(A.S.O./Billy Ceusters)

Stage two will start in Il Pirata’s hometown of Cesenatico and finish in the culinary capital of Bologna, featuring two ascents of the city’s famed San Luca climb – the scene of Fiorenzo Magni’s iconic time trial at the 1956 Tour, when the Italian clamped his teeth to an inner tube attached to the handlebars to help him steer and ease the pain of a broken collarbone.

Stage three to Turin, meanwhile, will take in Tortona, where Il Campionissimo, Fausto Coppi, died in early January 1960 after contracting malaria while racing in Burkina Faso. As the Tour crosses back over into France the following day, the riders will face the mighty Galibier, where Coppi attacked in the yellow jersey in 1952 to put the seal on his second Tour win.

So, to celebrate the Tour’s long-awaited first Grand Départ on Italian soil, here’s the seven men and two women who have carried the yellow jersey back across the Alps…

Ottavio Bottecchia (1924, 1925)

“Ottavio Bottecchia’s face has poverty and war written into it,” wrote John Foot in his excellent history of Italian cycling Pedalare! Pedalare!

Like so many other pro cyclists of the era, Bottecchia was born into a poor rural family in the Veneto and, after fighting for Italy during the First World War as part of its elite cycling divison (despite a later scandal concerning the authenticity of his Italian heritage), he sought to make a living racing his bike in the sadistic exercises that passed as grand tours in the 1920s.

In 1923, riding without a team, he finished fifth at the Giro d’Italia before – as a complete unknown outside his home country – winning a stage of that year’s Tour de France, leading the race for a spell, and finishing second behind Henri Pélissier, who christened Bottecchia as his successor.

That prediction would come true almost immediately, as Bottecchia became the first Italian Tour winner the following year, winning the first stage and holding the yellow jersey for the entire race. He’d follow that up in 1925 with four stages and another overall victory.

However, after abandoning the 1926 Tour in a thunderstorm, Bottecchia died in June 1927 in suspicious circumstances – he was found lying horribly injured next to his bike, which was undamaged, while out on a training ride. He died 12 days later.

A string of confessions emerged in the years after his tragic death, including those of a peasant enraged at the Tour winner stealing his grapes (despite the timing of his death contradicting that claim), an unlikely Mafia hit, and claims that he was targeted by fascists after Bottecchia refused to endorse Italian dictator Benito Mussolini.

Regardless of the confusion surrounding his death, 100 years after his and his country’s first triumph, Bottecchia’s legacy lives on at the Tour.

Gino Bartali (1938, 1948)

By now, the mythology surrounding Gino Bartali almost outweigh his achievements on the bike. There’s the rivalry with Fausto Coppi that divided a nation, symbolising Italy’s growing chasm between its conservative and deeply religious population and the country’s modern, secular elements in the wake of the Second World War.

There’s the story, heavily shrouded in myth, legend, and hearsay, that Bartali’s 1948 Tour win saved Italy, brought to the brink after Communist leader Palmiro Togliatti was shot by a right-wing student while leaving parliament, from civil war.

Then, there are the revelations that emerged following his death in 2000, of his apparent war-time exploits carrying messages in his bike frame – which the army would never have touched to avoid upsetting the great sporting icon – to the Italian Resistance. This role, some historians have claimed (though others have refuted, and which the cyclist never mentioned), may have saved hundreds of Italian Jews during the war (there are claims Bartali also hid a Jewish family in his house at one point), but remained a secret throughout the devout Catholic’s lifetime.

Even setting aside that added mythology, Bartali’s success on the bike – three Giri, two editions of the Tour (in 1938 and 1948, the biggest gap between victories), and some of the most dominant, iconic performances of an era in the mountains – would cement his status as an Italian cycling God.

Fausto Coppi (1949, 1952)

Il Campionissimo, the champion of champions, Fausto Coppi is never far away when a discussion of cycling’s greatest ever riders pops up.

An icon of style and staggering all-round ability, Coppi followed up his maiden Giro victory in 1940 at the age of 20 with four more editions of the Corsa Rosa (a record that no doubt would have been extended without the enforced break of the Second World War), three Milan-Sanremos, five editions of the Tour of Lombardy, a Paris-Roubaix, a world title, and two overall wins at the Tour de France.

His rivalry with Bartali split a nation into two camps (and led to farcical moments such as when the pair climbed off their bikes instead of cooperating at the 1948 Worlds), and his affair and divorce shocked it to its core and set in motion the birth of modern Italy. His death in 1960 of malaria brough Italy to a standstill.

But it’s the effortless style and otherworldly performances on the bike – his comeback win against the unfortunate Bartali in 1949, his dismantling of his rivals at the 1952 Tour in the Alps, a race he won by almost half an hour – that united Italy, as Coppi stood tallest as Italy dominated the post-war cycling world.

Gastone Nencini (1960)

The original demon descender (and forerunner of Vincenzo Nibali), a talented artist, and a chain smoker, Gastone Nencini won his home grand tour in 1957, before following that feat with his 1960 Tour de France triumph.

The Lion of Mugello achieved his greatest victory despite failing to win a stage and in the wake of Roger Rivière’s horrible, career-ending crash on a Massif Central descent, as the Frenchman tried desperately to cling to Nencini’s wheel.

Often the forgotten man of Italy’s Tour winners – and remembered more for the bad luck that saw him robbed of the Giro in 1955 than his actual victories – Nencini’s win in France was the peak of his career, as a crash the following year blunted his power just as he reached the top.

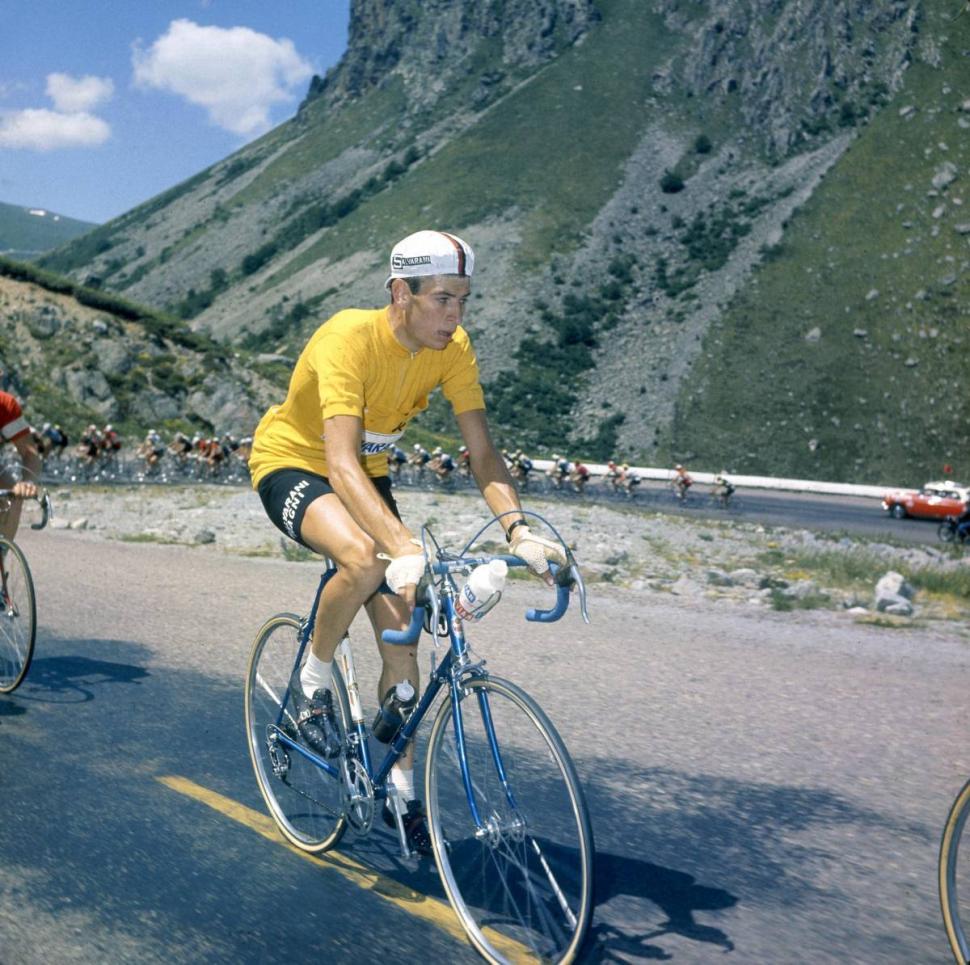

Felice Gimondi (1965)

Felice Gimondi’s Tour de France win, in 1965 at the age of 22 while ostensibly riding in support of Giro winner Vittorio Adorni, could well have represented the start of a new era in cycling.

The youngest post-war Tour winner until Egan Bernal in 2019, Gimondi went on to win the Giro three times and the Vuelta a España, becoming only the second rider to win all three grand tours, along a world title in 1973, Milan-Sanremo, Paris-Roubaix, and two Tours of Lombardy.

However, Gimondi’s career just so happened to overlap with a certain Eddy Merckx, condemning the Italian to the might Belgian’s shadow for the next decade. Still, 135 race wins while competing with Merckx isn’t too bad.

Marco Pantani (1998)

The sight of Marco Pantani, his arms spread out, Christ-like, looking every inch the fallen angel through the gloom at the top of Les Deux Alpes, the German machine Jan Ullrich put to the sword by old-school panache and verve at a Tour decimated by its own failings, symbolised an entire confused, murky era of pro cycling.

In many respects, to his fans Il Pirata – the last man to complete the Giro-Tour double – represented everything great about cycling. His pure climbing frame, his attacking instincts, his fragility, the feeling that you’re about to either witness history or disaster strike.

He stood out like a bandana-clad sore thumb in the controlled, asphyxiating environment of the 1990s and early 2000s, the throwback, romantic counterpart to the faceless, computer game stylings of Indurain, Ullrich, and Armstrong. Les Deux Alpes, Mont Ventoux, Alpe d’Huez – places indelibly linked to Pantani.

That his finest hour came in 1998, cycling’s nadir, is also fitting.

Pantani’s demise – the doping scandals, the meltdown, the cruel, pitiful end in a lonely hotel on Valentine’s Day in a barren seaside town – also represented the worst of a sport he defined in so many ways.

Vincenzo Nibali (2014)

The last truly great male Italian racer, the Shark of Messina’s 2014 Tour victory is almost a counterpoint to the chaos-fuelled attacking that characterised his later career. A stage-winning attack in Sheffield was followed up by possessing the coolest head (and the best legs) on a brutal, rainy day on the cobbles.

His biggest rivals, Chris Froome and Alberto Contador, may have fallen victim to crashes – but Nibali’s poise and dominance over that remained killed off any doubts that the Italian, at the top of his game, was a thoroughly deserved Tour winner, adding his name to the list of riders who have triumphed at all three grand tours.

Maria Canins (1985, 1986) and Fabiana Luperini (1995, 1996, 1997)

In a country not short on its female cycling pioneers – Alfonsina Strada remains the only woman to race one of the men’s grand tours, at the 1926 Giro – Maria Canins was one of the defining riders of the original stab at the Tour de France Femmes in the 1980s, the featherweight climber winning it twice and enjoying an epic rivalry with tainted French star Jeannie Longo.

Two-time Tour Feminin winner Maria Canins climbs the Col d'Izoard during the 1986 race

Five-time Giro winner Fabiana Luperini, meanwhile, won what was known as the Grande Boucle Féminine Internationale three times in the mid-1990s during a stunning stage racing career, laying the groundwork for the likes of Elisa Longo Borghini and Gaia Realini – the most likely successors to Italy’s Tour heritage – in the 2020s.

After obtaining a PhD, lecturing, and hosting a history podcast at Queen’s University Belfast, Ryan joined road.cc in December 2021 and since then has kept the site’s readers and listeners informed and enthralled (well at least occasionally) on news, the live blog, and the road.cc Podcast. After boarding a wrong bus at the world championships and ruining a good pair of jeans at the cyclocross, he now serves as road.cc’s senior news writer. Before his foray into cycling journalism, he wallowed in the equally pitiless world of academia, where he wrote a book about Victorian politics and droned on about cycling and bikes to classes of bored students (while taking every chance he could get to talk about cycling in print or on the radio). He can be found riding his bike very slowly around the narrow, scenic country lanes of Co. Down.

Latest Comments

- OnYerBike 18 min 42 sec ago

There's also the inference that bobbies on the beat are actually achieving something useful. My understanding is that the evidence suggests...

- mitsky 23 min 20 sec ago

I've never started AND ended a cycling commuting journey at the same place and time as another cyclist so I'm not sure how frequently that happens ...

- OnYerBike 32 min 10 sec ago

You're not missing anything - the article is wrong. It should be the "stack/reach" ratio. The rest of it then makes sense.

- Bungle_52 55 min 24 sec ago

A quick google brought up this...

- Steve K 1 hour 15 min ago

It would appear that soon you will be more likely to be banned from driving for benefit fraud than for a driving offence.

- Cugel 2 hours 10 min ago

Despite the ad-blocker message and the fact that I keep mine on, especially when gawping pointlessly at websites that do "reviews" such as this,...

- the little onion 2 hours 44 min ago

It's worse than apartheid.

- MikeLondonCommuter 3 hours 22 min ago

Have reported to police. It was registered but I forgot the code so have emailed bike register company hoping they can help.

- Eton Rifle 3 hours 21 min ago

Very sad news. She was a great voice for cycling on twitter. I deleted my account months ago for obvious reasons and couldn't find her on Bluesky.

- HKR 4 hours 9 min ago

I've been using the FlowBio S1 sensor for a while now. Yes, it's bloody expensive but I've hyperhydrosis so knowing how much I sweat and how much...

Add new comment

3 comments

A great read, thanks. Bartali is in any case one of the giants of the sport but what might he have achieved if the war hadn't intervened?

Pantani will always be my hero, superstar.

Real men back then pushing real gears, none of this high cadence crap.

You do know it still takes the same power output to go the same speed, no matter what the gear size/cadence? Just checking...