- News

- Reviews

- Bikes

- Components

- Bar tape & grips

- Bottom brackets

- Brake & gear cables

- Brake & STI levers

- Brake pads & spares

- Brakes

- Cassettes & freewheels

- Chains

- Chainsets & chainrings

- Derailleurs - front

- Derailleurs - rear

- Forks

- Gear levers & shifters

- Groupsets

- Handlebars & extensions

- Headsets

- Hubs

- Inner tubes

- Pedals

- Quick releases & skewers

- Saddles

- Seatposts

- Stems

- Wheels

- Tyres

- Tubeless valves

- Accessories

- Accessories - misc

- Computer mounts

- Bags

- Bar ends

- Bike bags & cases

- Bottle cages

- Bottles

- Cameras

- Car racks

- Child seats

- Computers

- Glasses

- GPS units

- Helmets

- Lights - front

- Lights - rear

- Lights - sets

- Locks

- Mirrors

- Mudguards

- Racks

- Pumps & CO2 inflators

- Puncture kits

- Reflectives

- Smart watches

- Stands and racks

- Trailers

- Clothing

- Health, fitness and nutrition

- Tools and workshop

- Miscellaneous

- Buyers Guides

- Features

- Forum

- Recommends

- Podcast

Aero vs lightweight road bikes with Ribble: How much faster could an aero bike make you?

This article includes paid promotion on behalf of Ribble Cycles

When it comes to choosing a new road bike or upgrading your components, you might find it difficult to decide whether to go for a bike that is primarily lightweight or one that is built for aerodynamics. So, what is actually faster?

This doesn't just apply to elite cyclists, but riders like you and I - amateur riders looking for more speed, for less effort. To find out what's best, we sat down for a chat with Ribble Cycles, creators of the no holes barred aero bike that is the Ultra SLR, to find out what makes a bike aero, and how much advantage it could give you.

On a lumpy ride around Lancashire, the home of Ribble Cycles, you might not think that the Ribble Ultra SLR, a true aero road bike, is the steed for the job. Compared to something like the Endurance SL R, this is a bike that isn’t particularly light. It’s safe to say that comfort or versatility aren’t high on the priority list either. You don’t even get bar tape!

And yet, when it comes to road racing, this is the bike that the Ribble Collective riders reach for. Why? Because apparently, it’s bloody fast!

The Ultra SLR is unapologetically aero. It doesn’t try to pretend to be 'one bike to do it all', and according to its designers puts speed above all else. Really, it’s the perfect bike to look at when comparing aero and lightweight.

Is aero important to you?

It’s fairly unanimously agreed that the key to speed on most flat and even rolling courses (every race in the UK then) is aerodynamics. The dark art of taming the wind can’t be seen, rarely heard and yet at road race speeds it’s almost entirely responsible for the resistance you face.

We’re told that a lot, but most of us can’t ride at the same speed as the pros. So, does it still matter to us? Well, we managed to drag some experts from Ribble out of the wind tunnel, armed with years worth of data to answer that very question.

Andy Smallwood, CEO of Ribble Cycles, told us: "Aerodynamics is crazy important for a cyclist. 80% or more of your efforts, no matter what you're putting in through the pedals, goes into moving air out the way."

"It's vitally important that you factor in aerodynamics with regards to bike design. And that's not just for the rider who's competing to win the Tour de France. It's me, it's you, it's somebody who's commuting to work and back."

"No matter what cycling you are doing, 80% of what you do, the effort you put in is moving air out the way."

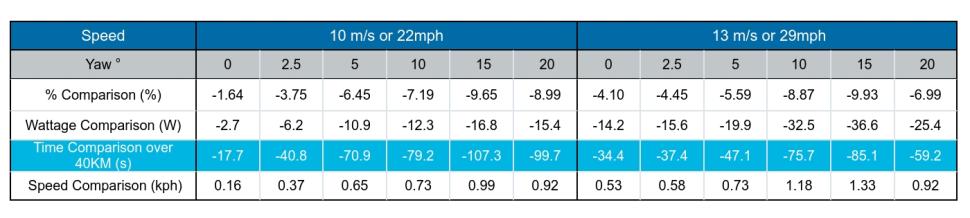

Jamie Burrows, Ribble's Head of Product, explained that for the Ribble Ultra SLR, the brand's most advanced aero bike, the testing was purposefully based around what they call "enthusiast and pro levels, riding at 22mph and 30mph.

"It was key to design a bike that was yes, great at pro speeds, but also great at lower speeds as well," says Burrows.

"The testing we did actually showed that the enthusiast level at 22mph actually performed better than the pro at 30mph."

So yes, even if you're not a speed freak, aerodynamics do play a role at amateur-level speeds. According to Ribble's data, it's us that could benefit most from an aero bike.

Can a bike's aerodynamics actually make a difference?

My next question to Ribble was how much of that drag can actually be influenced by the bike. Look at the frontal profile of a bike and rider, and a very small percentage of the frontal area is actually the bike. Therefore, is even the most aerodynamic bike not going to make a negligible difference?

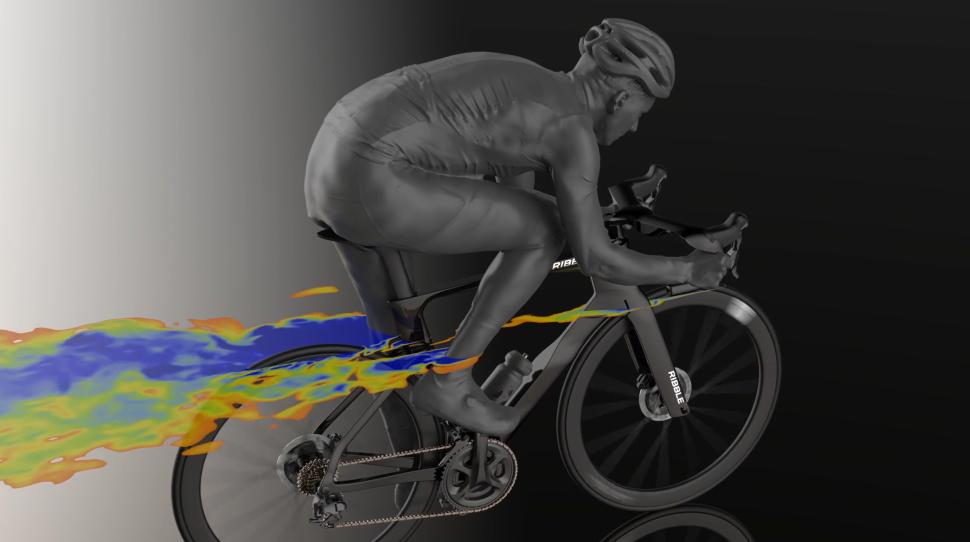

Ribble responded: “As we progressed through the project it became very evident that the aerodynamics of the bike have a significant positive or negative impact on the rider, particularly on elements of the bike that are directly downstream of the rider.

"Through this analysis, we examined in minute detail how the airflow from specific areas of the bike can be manipulated upstream (in front of the rider) to maximise their positive aerodynamic impact on the rider downstream.”

This is nowhere more clear than at the handlebar. Smallwood explained that while what we learnt in physics is true, "...thinner and slipperier is better on its own.

"The crucial thing here is that a bike is never in isolation and therefore when it comes to the whole testing process, it's absolutely fundamental that you take into consideration that the bike always has a rider on it.

"You've got these two wake generators underneath and what they effectively do is create a wake that directs [the air] around the rider's legs, and then exits to the side of the rider."

That's key, because a lot of your drag comes from your legs as you ride along.

So yes, while it is true that the bike makes up only a small proportion of your drag, bike brands like Ribble can design a bike to not only influence its own drag, but also reduce the drag of the entire system.

How do you actually make a bike aerodynamic?

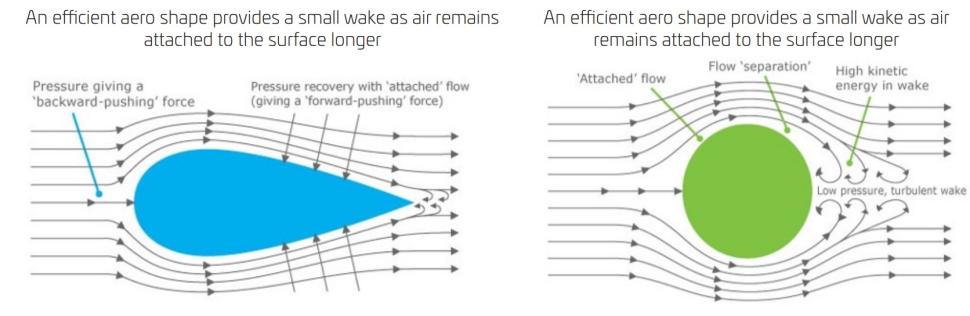

What I’m probably going to do here is make the Ribble boffins wince with my oversimplification of aerodynamics, but here goes... let's first imagine a single tube. It could go anywhere on the bike, the head tube or seat tube, for example.

Bikes used to have tubes that were the shape on the right (below) but the problem is that it’s quite draggy. It has a high coefficient of drag because the air causes a big wake behind it.

We obviously don’t want drag. It’s not really much good for anyone, imagine how much fun cycling would be if you always had a tailwind! Advances in materials and carbon fibre have meant that for the last few decades, mainstream bikes can benefit from tubes of a more aero shape. For example, the aerofoil (above, left) has a much lower cDA (coefficient of drag).

And that’s why wherever you look on a bike like the Ultra SLR, each tube profile has a story to tell. The bar that we mentioned earlier is actually designed to cause a bigger wake around the rider, while the fork is just 15mm thick but 68mm deep to reduce any disturbance of the air as it passes through it.

It sounds simple, but trying to balance the aerodynamics of tube profiles with the structural stiffness, strength and interaction with rider takes a lot of work. In the case of Ribble, this happens using CFD (computational fluid dynamics), in a wind tunnel, and with real-world testing as well to validate the results.

"A bike that is only fast in a wind tunnel is pointless"

During my time at road.cc, I've had the chance to ride both slow bikes and very fast bikes, so I was keen to understand how a brand can ensure that their latest creation is going to perform in the real world as intended.

"From CFD, all the way through to real-world testing on average, we were 0.04% aligned across the whole process. Yaw angle is very important when it comes to real-world cycling", says Smallwood.

"Yaw angle is effectively, the degree of crosswind that you are encountering as you are cycling.

"It is very rare that you are riding with a full-on headwind directly in front of you. You'll have a degree of crosswind that will be hitting you and that is, essentially, called the yaw angle."

This is important because, in the real world, a bike that is very aerodynamically effective at zero degrees of yaw could behave very differently as you go into a slight crosswind.

"One of the hardest parts of this project was actually how can we keep the benefit as we go through the yaw sweep i.e right the way from headwind, all the way through to a crosswind of up to 15, 20 degrees.

"The whole point was to have a bike that was a real-world bike with a sweet spot of around 5 to 10 degrees. And what we actually saw was when we hit 15 degrees of yaw, which is obviously quite a steep angle of wind, but not uncommon in the UK, the bike shape actually creates a thrust and actually gets faster."

There are also other factors to consider when designing a bike to be fast in the real world.

Smallwood explained: "Pretty much everybody is gonna be riding this bike with a water bottle on it. So what we did was we optimised the down tube for the shape to be specific at different points of the down tube in how it reacts with different elements that are going on around it. So actually what we've got is we've got a frame here, which is faster with a water bottle than without a water bottle."

So is an aero bike faster?

It's easy to forget when looking at how much work has gone into making the Ultra SLR as fast as possible that Ribble still sell a lightweight all-round climbing bike, the Endurance SLR. So, which one do they say is fastest?

Smallwood says: "In the vast majority of cases, if it's all about performance, the Ultra SLR, the most aero bike wins. It's only when you get to a pure uphill climb over a certain percentage, and your speed is low as well, that the low weight really starts to edge ahead. But generally aero trumps lightweight.

"It's not all about going faster but can be about efficiency, it works both ways. If you've got a wattage saving, you can even use it to go faster or you can use it to put less effort in, and maintain the same speed."

But how much faster?

When compared to the Endurance SLR, which represents a lighter, more conventional all-rounder frame, the unapologetically aero Ultra SLR will save the pros 61.4 seconds over a flat 40km, and potentially even more for riders like me and you.

We’re well used to claims like that from brands trying to plug their latest aero bikes, but it’s refreshing to see an entire white paper of numbers detailing wind conditions, and the time you can expect to save vs another bike in Ribble's range. This isn't some 1980s contraption either, it's an aerodynamically optimised race bike with an integrated bar and stem.

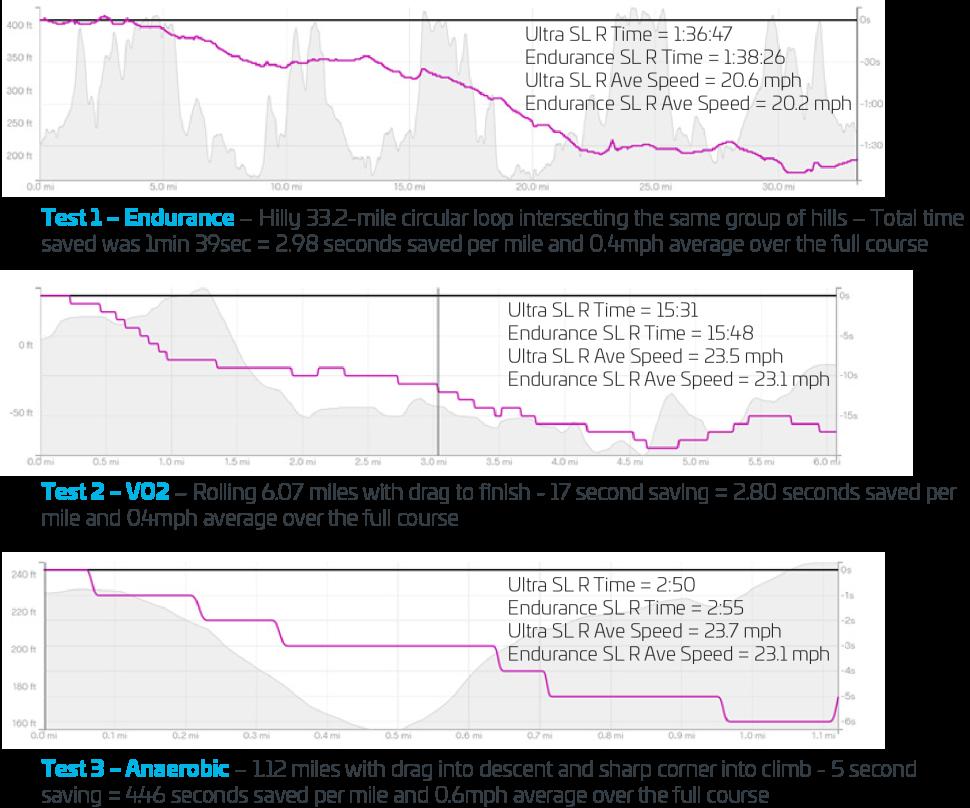

Ribble gave us access to their real-world test data from three tests that were conducted over multiple courses with different distances, terrain profiles and types of effort, ranging from 1.5-hour Threshold Endurance, 15-minute VO2 and even a 3-minute Anaerobic test where stiffness may also play a role.

What we can glean from this is that unless you’re a hill climber, or you enjoy putting in more effort for less speed, then aero is probably the way to go. The tests show that the Ultra SLR is around 0.7kph faster than its lightweight counterpart. An out-and-out aero bike could save you up to around 4.5 seconds per mile, which could make those PRs and Strava segments much easier to smash!

So... aero or lightweight?

Why do we all have an obsession with lightweight bikes then? Perhaps it’s because weight is so tangible. Pick up a bike and you can immediately tell if it’s lightweight or not, we all do it! These days we might have a vague idea of what an aero bike looks like, but actually measuring aerodynamic efficiency is a lot more difficult. You need a wind tunnel and/or CFD (computational fluid dynamics) software.

You can’t pick up your mate’s bike before a ride, whistle through your teeth and tell how aero it is - but after chatting to these guys, I know that I’d be prepared to ride a bike that weighs an extra kilogram compared to the lightest road bikes in the name of cheating the wind.

If this article has whet your appetite to find out more about the Ultra SLR, then you can check out the full range of aero builds on the Ribble website using the link here, plus all the engineering white papers to explain the science behind the speed.

Jamie has been riding bikes since a tender age but really caught the bug for racing and reviewing whilst studying towards a master's in Mechanical engineering at Swansea University. Having graduated, he decided he really quite liked working with bikes and is now a full-time addition to the road.cc team. When not writing about tech news or working on the Youtube channel, you can still find him racing local crits trying to cling on to his cat 2 licence...and missing every break going...

No. Within a very short period of time, the RRP on these items will have ratcheted up to where they were before, with the exchequer not getting VAT...

As witnessed at so many infrastructure improvement projects similar to this one, all those who object should ignore the consultation and pray at...

It's a DLO to those in the trade.

Surely as a former bridleway these should be equid-based e.g. "hoof-depth" / "up to the fetlock" / "approaching hock/knee"?...

Cars keep getting wider and wider, but it's those damn cyclists with their wide handlebars that are the real problem. ref

"it's almost entirely from recycled composite materials". What percentage of the carbon frame is made from recycled carbon?

Motorist Mike demands 40p back after overcharged on new £11m 'prison' car park...

I have two aero bikes- an Argon18 Nitrogen and an Orro Venturi. I love the way they feel on the road. I also like the style of the deeper section...

They have here: results at 14.40. The aero bike was roughly fifteen seconds faster than a climbing bike on a descent of around 6 km, so about 3km/h...

As I've also placed here the nutter Audi and white van drivers, I've decided to give those no-nonsense keep-the-country-moving BMW drivers a list...