- News

- Reviews

- Bikes

- Components

- Bar tape & grips

- Bottom brackets

- Brake & gear cables

- Brake & STI levers

- Brake pads & spares

- Brakes

- Cassettes & freewheels

- Chains

- Chainsets & chainrings

- Derailleurs - front

- Derailleurs - rear

- Forks

- Gear levers & shifters

- Groupsets

- Handlebars & extensions

- Headsets

- Hubs

- Inner tubes

- Pedals

- Quick releases & skewers

- Saddles

- Seatposts

- Stems

- Wheels

- Tyres

- Tubeless valves

- Accessories

- Accessories - misc

- Computer mounts

- Bags

- Bar ends

- Bike bags & cases

- Bottle cages

- Bottles

- Cameras

- Car racks

- Child seats

- Computers

- Glasses

- GPS units

- Helmets

- Lights - front

- Lights - rear

- Lights - sets

- Locks

- Mirrors

- Mudguards

- Racks

- Pumps & CO2 inflators

- Puncture kits

- Reflectives

- Smart watches

- Stands and racks

- Trailers

- Clothing

- Health, fitness and nutrition

- Tools and workshop

- Miscellaneous

- Buyers Guides

- Features

- Forum

- Recommends

- Podcast

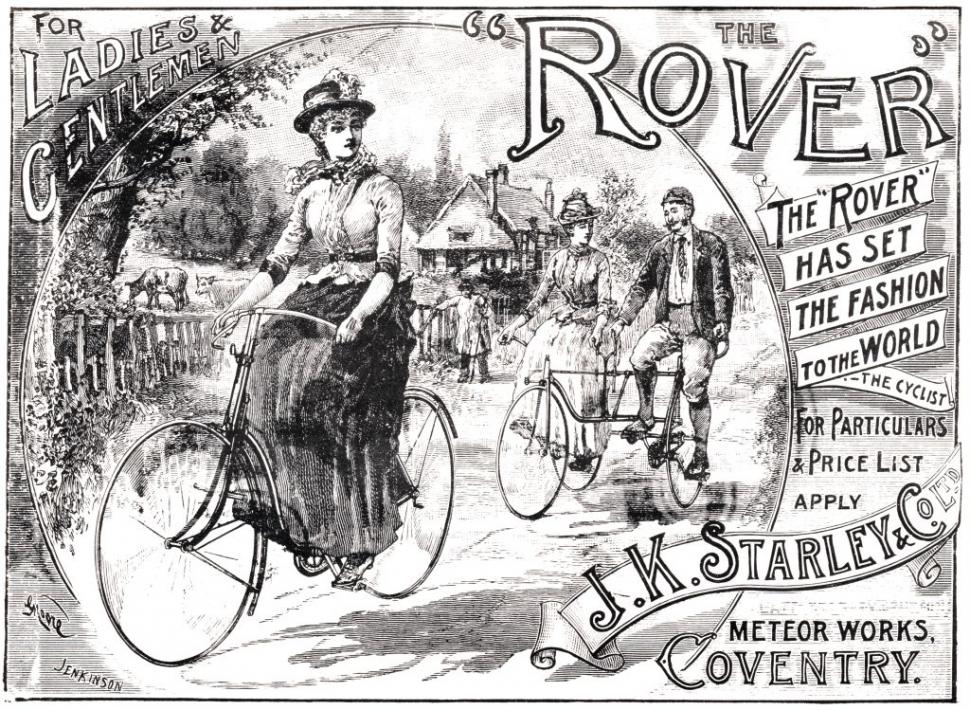

An early ad for the Rover Safety (Wikimedia Commons).jpg

An early ad for the Rover Safety (Wikimedia Commons).jpgCycling revolutions: 10 brilliant inventions that changed the bicycle forever

The Design Museum ran an exhibition in 2016 called ‘Cycle Revolution’ that celebrated major steps in cycling technology. But its selections, while unarguably interesting, didn’t really represent the revolutionary stages in the history of the bike. Here are the inventions that truly revolutionised cycling.

The Laufmaschine

The spark of genius that started it all landed in the head of German inventor Karl Drais in about 1817. (Technically he was Baron Karl Von Drais at the time, but his radical political leanings meant he later dropped the title.)

Europe had had several years of poor harvests, pushing up the cost of oats and making it it prohibitively expensive to keep horses for transport.

Searching for a replacement that didn’t need feeding, Drais hit upon an idea he called the Laufmaschine (running machine), later also known as velocipede, draisine, hobby horse or dandy horse. The rider sat astride a crossbar between two wheels and pushed along the ground to go forwards. It was exactly like a modern kid’s balance bike.

Drais’ genius was in realising — or discovering — that two wheels in a line would not simply fall over if there was a steering mechanism for the front wheel, but would be relatively stable once in motion. To demonstrate his device’s merits, he completed the 15km round trip from Mannheim to Schwetzingen and back in a little over an hour.

Unfortunately, early 19th century roads were too rutted for the Laufmaschine to be practical for any distance, even though Drais had showed it to be quicker than walking on good surfaces. Riders used the sidewalks instead, and governments reacted to pedestrian anger at the influx of fast-moving dandies by banning the machine.

Pedals

The idea of two-wheeled transport slept for about forty years until the 1860s when bicycles with pedal-driven front wheels appeared in Paris and the Eastern USA. Exactly whose idea this was is still a subject of research among cycling historians but it’s clear that Rene Olivier and his brothers, and a young French mechanic called Pierre Lallement were the among pioneers.

Pedal drive meant the rider didn’t touch the round at all while riding, a phenomenon that amazed contemporary onlookers. With the blacksmith Pierre Michaux as figurehead, the Olivier brothers orchestrated a craze for bicycles in Paris, while American makers of bikes based on Lallement’s design struggled to keep up with demand.

Pedals freed riders from the cumbersome action of pushing along the ground and allowed speeds of 12 mph, and more with larger wheels. A vehicle we’d recognise as a bicycle had arrived.

The tension-spoked wheel

Wheels with wire spokes under tension were invented in 1808 by aeronautical engineer George Cayley, but their first successful commercial use was on bicycles, an application for which Eugène Meyer was awarded a patent in 1869.

Wire wheels were substantially lighter than solid-spoked wheels, which made bicycles a compelling application, especially as wheel sizes grew to provide riders with a higher gear for faster riding. As with bearings, chains and high-strength steel, cycling applications drove the development of wheel technology.

The roller chain

The large driven wheels that led to the high-wheeler bikes of the 1870s weren’t the only way of increasing a bike’s gearing. It was obvious that a chain drive and sprockets could do the job too, but early chains were heavy, inefficient and unreliable. The breakthrough came in 1880 with Hans Renold’s invention of the roller chain and improved manufacturing techniques that allowed chains to be mass-produced.

The safety bike

To differentiate them from hazardous high-wheelers, bikes that placed the rider near the ground were called ‘safeties’ and began to appear in the late 1870s. The first truly successful safety, though, was John Kemp Starley’s 1885 Rover safety, which incorporated the essential features of a modern bike: similar-sized, wire-spoked wheels and chain drive to the rear wheel.

The safety was a genuine revolution. By reducing the risk of going head-first into the ground if you crashed, the safety allowed everyone to ride a bike, not just the young, brave and athletic.

In time, Starley’s company became Rover Cycle Company Ltd and after Starley’s death branched out into motorbikes and cars. It survives today as Jaguar Land Rover Limited after numerous sales and take-overs.

Pneumatic tyres

Contrary to popular belief, John Boyd Dunlop wasn’t the original inventor of the pneumatic tyre; Robert William Thomson filed a patent in 1845. Dunlop’s application of pneumatic tyres was nevertheless revolutionary even though his lack of a valid patent made it harder for him to exploit the idea.

Tyres had previously been made of solid rubber, giving a harsh ride, a problem that was partly alleviated by the huge wheel of a high-wheeler, but which was severe on safeties. By putting a cushion of air between the road and the rider, Dunlop made the safety comfortable as well as safe. And there was another advantage: pneumatic tyres were lots faster, thanks to their lower rolling resistance. When so-so riders on pneumatics started beating elite racers on solid tyres, racers quickly switched.

Hub gears and the parallelogram derailleur

Two brilliant approaches to the same problem: metering out the human engine’s meagre couple of hundred watts so a rider can get up hills slowly and comfortably on the same bike that speeds along at 20mph on the flat.

Epicyclic gears with interlocking cogs to provide different ratios are at the heart of hub gears. They first appeared on tricycles in the mid-1880s, but they rocketed to popularity after Raleigh head Frank Bowden bought the rights to two different three-speed designs and appointed Henry Sturmey and James Archer to head a division that began to make the Sturmey-Archer three-speed hub in about 1903.

The hub gear was wildly popular in the UK for its simplicity of use and minimal need for maintenance. It provided easier hill-climbing and greater speed on the flat, once again opening up the use of the bicycle to a wider range of people and abilities. With the introduction of the AW hub gear in 1936, Sturmey-Archer enabled the heyday of the classic English three-speed beloved of vicars, policemen, district nurses and factory workers of the era.

But more adventurous riders wanted more gears and a wider range. French cyclists in particular, faced with the challenge of long and steep Alpine roads, experimented with a huge variety of gear-changing systems. Eventually they settled on the derailleur, a device that literally de-railed the chain between multiple sprockets.

But it took literally decades of development and refinement for the derailleur to reach its modern form. On the way, inventors such as Velocio came up with a huge variety of ingenious contraptions involving cages to shove the chain around, one or two pulleys to take up chain slack, wheels that moved in the dropouts and many, many more.

The first recognisably modern derailleur, with two pulleys on a tension arm and a parallelogram body, was made by Nivex in France in 1938. Another French company, JIC, had a similar design in 1946. Neither company survived. Cycling historian Frank Berto puts that down to the high price of their components, which seem to have been built up to a standard rather than down to a price.

Credit for the first commercially successful parallelogram derailleur goes to Tullio Campagnolo, who introduced the Gran Sport derailleur in 1951. Being Campagnoloishly expensive it wasn’t an overnight smash hit, but over the next decade or so copies of the design gradually edged out other derailleurs.

In fact the Gran Sport wasn’t even terribly good compared to the Nivex and others. It came to dominate because of Campagnolo’s prestige and support of racing. The Gran Sport’s main problem was that the top jockey was a long way from the sprockets, so the rider had to overshift and then correct, to allow for the sideways flexibility of the chain.

Nobuo Ozaki of SunTour solved this problem with the slant parallelogram derailleur patented in 1964. When the patent ran out 20 years later, first Shimano then other derailleur manufacturers including Campagnolo adopted it.

The Moulton

Sometimes a bike is revolutionary not for its technical advances but for how it fits the zeitgeist. With its small wheels and novel looks the original Moulton bicycle was as much a part of Britain’s swinging ’60s as the mini-skirt and Mini car.

As they rushed out small-wheeled lookalikes, other bike makers entirely missed the point of the Moulton’s combination of features. Yes, it had small wheels, but they had relatively narrow, high-pressure tyres, a combination that would be uncomfortable but for the Moulton’s rubber suspension.

Rubber was the basis of the Moulton family fortune. Stephen Moulton first brought samples of vulcanized rubber to the UK; his great grandson Alex Moulton designed the rubber-spring suspension system for the Mini car, and then turned his attention to bicycles. The Moulton begat a wave of small-wheeled bikes and changed the look of commuting cycling. Can you imagine the Brompton being as easily accepted if Moulton hadn’t blazed the trail?

Breezer mountain bike

Like so many cycling revolutions, the mountain bike happened because several people and ideas came together at the right time. Gary Fisher provided the marketing nous, Charlie Kelly the spirit and Joe Breeze and Tom Ritchey the frame-building skill. While Tom Ritchey built most of the bikes sold in the early days of Mountain Bikes the company, Joe Breeze meticulously welded the first ten, igniting demand from those who saw them.

Charlie Kelly has written that the first Breeze mountain bike was the most important bike of the 20th century. In a 2014 interview with Velonews, he said: “That bike inspired three or four other people. That was the pebble coming off the top of the hill that became an avalanche, but when you look at the modern mountain bike, working your way upstream, that’s where it hits, with that Breezer bike.”

The mountain bike boom of the ’80s and early ’90s brought a generation back to cycling that might have otherwise abandoned it; opened up the countryside to a new, fun way of exploring; and facilitated urban cycling with pothole-proof bikes that had much better brakes and riding position than road bikes of the day.

Honourable mentions

These are important inventions that shaped cycling — especially sport cycling — but it’s a stretch to call them revolutionary.

Freewheel The ratcheting mechanism that lets a wheel spin without turning the pedals was invented in 1869 by William Van Andenin but was initially disdained by cyclists who feared adding mechanical complexity to the early bicycle. It reappeared with the advent of coaster brakes and multiple gearing.

Lycra Readers with long memories will recall ghastly shorts made from wool and other knitted fabrics in the pre-Lycra era. They were heavy and sweaty and only used by riders doing the sort of long distances that demanded a chamois liner. Stretchy fabrics using Dupont’s Lycra fibre were a huge improvement in comfort, moving with the rider and making cooling much easier.

Indexed gears Shifting that clicks from gear to gear had been around for decades when Shimano introduced SIS gearing — it’s how all hub gears work. But Shimano realised it could be an advantage for racers, who would fluff shifts when tired. Indexed down tube levers and mountain bike thumbshifters led to integrated brake/shift levers. I often wonder if the road bike boom of the last few years would have happened without gears you could change with your hands still on the bars..

Clipless pedals In the days of clips and straps a common way to fall over was to roll up to lights and discover, far too late, that your straps were so tight you couldn’t get out to touch a foot down. Clipless pedals eliminated that embarrassing tumble, while also improving comfort and, with recessed-cleat SPD pedals, ushering in a combination of efficiency and walkability.

LED lights The light-emitting diode has made it cheap and easy for cyclists to be seen at night, and to see where we’re going. The only option before LEDs was a dim, unreliable glimmer of light from a torch powered by a pair of hulking great D cells. These lights chewed through batteries, so were expensive to run, especially if you decided you actually wanted to be seen and fitted a halogen bulb. Reliability was also awful; cheap, rattly switches corroded if they got damp and in trying to keep the price down manufacturers neglected to pay much attention to sealing out the weather.

The combination of high-power LEDs and improved rechargeable batteries made better front lights possible too. Night riding on unlit lanes became possible and drivers had a whole new excuse to complain about cyclists — our lights are now too bright, apparently.

John has been writing about bikes and cycling for over 30 years since discovering that people were mug enough to pay him for it rather than expecting him to do an honest day's work.

He was heavily involved in the mountain bike boom of the late 1980s as a racer, team manager and race promoter, and that led to writing for Mountain Biking UK magazine shortly after its inception. He got the gig by phoning up the editor and telling him the magazine was rubbish and he could do better. Rather than telling him to get lost, MBUK editor Tym Manley called John’s bluff and the rest is history.

Since then he has worked on MTB Pro magazine and was editor of Maximum Mountain Bike and Australian Mountain Bike magazines, before switching to the web in 2000 to work for CyclingNews.com. Along with road.cc founder Tony Farrelly, John was on the launch team for BikeRadar.com and subsequently became editor in chief of Future Publishing’s group of cycling magazines and websites, including Cycling Plus, MBUK, What Mountain Bike and Procycling.

John has also written for Cyclist magazine, edited the BikeMagic website and was founding editor of TotalWomensCycling.com before handing over to someone far more representative of the site's main audience.

He joined road.cc in 2013. He lives in Cambridge where the lack of hills is more than made up for by the headwinds.

Latest Comments

- ROOTminus1 1 sec ago

I'm glad the article went into more detail and cleared things up, the headline had me worried that some autonomous building had run rampant and...

- mark1a 18 min 32 sec ago

Still here, just showing a few signs of wear and tear. Hopefully still serviceable for some years to come.

- Secret_squirrel 48 min 24 sec ago

Has he fully recovered though, and will he ever?...

- Rendel Harris 1 hour 3 min ago

How can you know that you are "equally fearful" as "any female cyclist"? There is no possible way of quantifying such emotions and female cyclists...

- chrisonabike 1 hour 35 min ago

I think it would be fairer to blame the moon - as in "my client is a loony".

- Bungle_52 1 hour 58 min ago

Nice idea but Gloucestershire Constabulary are not interested as exemplified by this prvious NMOTD. Not only was there NFA for the close pass in...

- hawkinspeter 3 hours 30 min ago

I think black boxes are great for early detection of cognitive decline and/or sight problems. Someone's driving is going to become much less smooth...

- Bigtwin 4 hours 5 min ago

It's a fashion. https://guildford-dragon.com/shalford-driver-who-smashed-shalford-war-me...

- MTL Biker 4 hours 26 min ago

Robin Phans .....

Add new comment

50 comments

The good bike had been off the road for most of the summer, there was an oil leak from one leg of the suspension. Luckily the 40p No 10 "o" ring from the local hardware shop solved it, but if it had been slightly odd, then no more suspension. Or at least until I found a massive range of "o" rings, like the old workshop at my old work had.

Suspension is a wonderful thing, but it can add a massive level of complexity to what is the beautiful simplicity of the diamond bike frame. Rear pivot bushings do not do that well in our wonderful climate, requiring maintenance and costly replacement. This is an area where design and standards move very quickly, creating very speedy redundancy. My Marzocchi Z2 BAMs (99s?) pair incredibly well with my 96 Raleigh SPD 650 ti frame, but within 5 years it became difficult to replace with anything new, with a very limited choice, after 7 impossible. 3 inches of travel and a straight 1 1/8 inch steerer. I can still get seals, thank goodness, but if it dies, or I kill it when doing it's regular and required sevice, that's it for for my front end suspension.

My new build will be fully ridgid, indeed it does not have suspension adjusted geometry, lowering the front end.

I am surprised how _little_ the bike has changed, in 100 years, especially in shape. Why aren't they all suspended? Why so few recumbents or carbon city bikes? As for city bikes, why do they keep having large and heavy wheels that make them so inneficient? And those chains??? In fact there is little progress because the bike market is driven, depending on segment, by low retail prices, marketing & high margins, UCI regulations, and patents.

I know this is an ancient comment, but I'll reply...

Isn't the bicycle - certainly the 'city/utility bike' - driven by wanting simple, robust, easily-repaired technology? Hence fewer full-suspension carbon bike wotsits with hydraulic disc brakes, electronic shifting, and a cupholder.

Surely the helmet gets a mention, not only has it saved millions of lives, but also raised more than one from the dead. A truly awesome piece of kit.

You are Donald "Sarcastic" Trump, and ICMFP.

Keeping illuminated whilst doing a morning paper round in the mid eighties was a constant battle with crap batteries and crap lights. The requirement to have orange reflectors on your pedals dates from this time when the authorities worked out that using moving reflectors picked out in car highlights was the most reliable way of illuminating cyclists

In the late 60s, I had a BSA . The lights were powered from a bottle dynamo. I think that fewer cars and slower speeds meant that lights were not so important, at least in the cities.

For me the springiness of the switch mechanism woud die so I would bend them in to make permanent contact and I would remove the lens unit to turn them off. I am so pleased that lights have gotten good.

It all got a bit better with the AA battery units, cateye incandesent on the back, dim but very well made and a Specialised 2.5 halogen on the front. Ran duracells initially at about 10p a mile, early 90s, but then moved onto rechargeables. Even fitted a second on the front, for those dark cycle routes.

And i remember having to get the sand paper on the contacts as they used to rust. Terrible things and i think the police used to take a lenient view on not having lights as they cost a fortune to run

I never did understand how EverReady got away with selling those shite lights of theirs for so many years we just put up with it and kept buying replacements!

Yes, I got mine to replace the excellent Wonder lights, batteries were difficult to get hold of. The ever readys were the ones with the easy release brackets, D cells. They were incredibly brittle and the switch would become unusable after a bit. And then you would have to get a new one.

The Dandy Horse was not banned from the road, it was banned from the pavement. A scour through the British newspaper archives shows prosecutions for riding on the pavement dating from 1819, when the craze hit the UK. Leather britches were advised and use of the machine quickly wore through boots. Dandy horses were used well into the 19th Century by workmen who had to travel in their business.

One version of this machine was called the 'velocimanipede'. It anagrams to 'I can impede love'.

Still a theory erroneously put about by some relating to two wheeled vehicles.

As a kid I cycled on an old Raleigh bike my Dad gave me, it had down tube shifters an toe straps. When I got my first bike bought for me in '88 it still had a 5 speed rear cog 2 at the front. Still used down shiters but had flat pedals.

I missed the toe clips so much I saved and bought some. Stopped cycling a few years later as I left school and found girls and other things.

Got a bike last year as a way to get fit and now have indexed gears, clipless peadals and shoes and wear bib shorts with padding... It is such a change from 20 years ago.

As much as I would not want to go back to riding for hours without 'all the mod-cons' I will be getting a single speed bike for my first N+1 as I miss being able to just hop on a bike and go for a spin tho

you forgot disk brakes *runs and hides*

What @kilOran said. Although, downtube friction shifters seem like a thing of beauty if you try them now. So simple and needing no adjustment. But agree re. brakes and toestraps. The brakes were hopeless because they acted on chromed steel rims. So you could add:

Aluminium rims

Previously bikes had used wooden rims, painted rolled steel rims, or even worse, chromed steel rims. Brakes worked very poorly on all these. Most ordinary single speed bikes had coaster brakes but if you had a three-speed hub then you were left to the mercy of hopeless rim brakes. The widespread adoption of aluminium rims from the 1990s on meant caliper brakes were reliable and effective.

In a way you can see the whole journey as a commercial one led by tech - the aim being to get more people cycling. High-wheelers to safeties and then to heavy bulletproof SA 3-speeds.

When I stopped cycling in the late 80s I had a "racer" with heavy D-cell EverReady lights, 10 non-indexed gears with downtube shifters and toestraps on the pedals. The brakes were useless even with the addition of suicides.

All that stuff meant you needed to be a good cyclist to not end up on the floor on a regular basis - I certainly recall unbridled hatred of downtube shifters which was why a brief affair with a Nexus 7-speed was so awesome.

25 years later on return to cycling I'm on 22-speed indexed electronic gears, dyno front light that means I can see in real country dark, SPDs, excellent brakes, etc. I'm astounded that I can arrive at the bottom of a hill and dump the chain 4 or 5 cogs with a single press of a microswitch.

The point is that pretty much anyone can hop on a road bike these days with limited skill and the bike will do very little to kill them. It will also be easy to maintain and relatively cheap to run as a result. First time I rode an STI bike I was completely amazed at the quality and ease of the shifting.

"Clipless pedals In the days of clips and straps a common way to fall over was to roll up to lights and discover, far too late, that your straps were so tight you couldn’t get out to touch a foot down. Clipless pedals eliminated that embarrassing tumble"

I wouldn't say "eliminated", perhaps "Clipless pedals reduced the frequency of occurence such that tumbles are now much more humourous for those fortunate to be watching"

Yep watched my mte fall off twice last weekend!

Cold Drawn Steel Tubes? Developed for water tube boilers in the late 1800's proved ideal for bike frames. In fact Arthur Yarrow, who helped develop the water tube boilers, claimed in an interview in the 30's that cold drawn tubes helped female emancipation as they could escape their chaperones on the new light bicycles!

Pages