- News

- Reviews

- Bikes

- Components

- Bar tape & grips

- Bottom brackets

- Brake & gear cables

- Brake & STI levers

- Brake pads & spares

- Brakes

- Cassettes & freewheels

- Chains

- Chainsets & chainrings

- Derailleurs - front

- Derailleurs - rear

- Forks

- Gear levers & shifters

- Groupsets

- Handlebars & extensions

- Headsets

- Hubs

- Inner tubes

- Pedals

- Quick releases & skewers

- Saddles

- Seatposts

- Stems

- Wheels

- Tyres

- Tubeless valves

- Accessories

- Accessories - misc

- Computer mounts

- Bags

- Bar ends

- Bike bags & cases

- Bottle cages

- Bottles

- Cameras

- Car racks

- Child seats

- Computers

- Glasses

- GPS units

- Helmets

- Lights - front

- Lights - rear

- Lights - sets

- Locks

- Mirrors

- Mudguards

- Racks

- Pumps & CO2 inflators

- Puncture kits

- Reflectives

- Smart watches

- Stands and racks

- Trailers

- Clothing

- Health, fitness and nutrition

- Tools and workshop

- Miscellaneous

- Buyers Guides

- Features

- Forum

- Recommends

- Podcast

feature

Puy de Dôme returns to Tour de France (GCN-Eurosport)

Puy de Dôme returns to Tour de France (GCN-Eurosport)Tour de France finally returns to legendary – and brutally steep – Puy de Dôme after 35-year absence

One of cycling’s dormant legends, the Puy de Dôme, will explode back into life at next year’s Tour de France. The Massif Central’s mythical dome-shaped volcanic plug, jutting high above Clermont-Ferrand, will make its first appearance at the Grande Boucle for 35 years on stage nine of the 2023 Tour, organisers ASO confirmed at this morning’s route presentation in Paris.

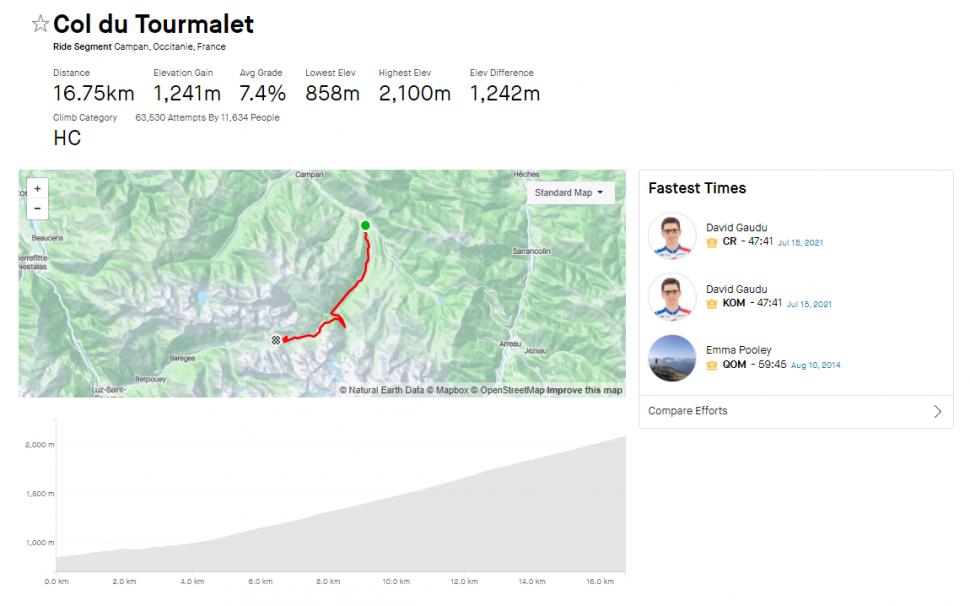

The race’s return to the Puy de Dôme, long thought impossible by the construction of a rail line, shrinking the road, in 2012, will form the centrepiece of what will surely be a men’s Tour for the climbers, featuring only 22km of rather hilly time trialling. Both the men’s and women’s races (which are previewed below) will tackle the iconic Col du Tourmalet, as the Tour de France Femmes ventures into the Pyrenees after last year’s focus on the Vosges.

Though the men’s route contains more than its fair share of climbing – including a prolonged, almost week-long stay in the Alps – all eyes will be on a volcano in the middle of the country long thought to be extinct, in racing terms anyway.

Ask any pro cycling fan, ‘what’s the most romantic, emblematic Tour de France climb?’, and you’ll get a dozen or so different answers and opinions. Most of which will be wrong.

It’s not Alpe d’Huez, the ‘Wembley of cycling’, a climb so gainfully employed by the Tour since the 1970s that it became almost too familiar, to the extent that race organisers ASO have reduced it to a freelance role in recent years. What about the doyennes of the Alps and Pyrenees, the Galibier and the Tourmalet? Nah. Mont Ventoux is certainly in with a shout, its occasional use and aura allowing it to retain its inherent sense of mystique and drama.

Today's nostalgia:

1964 Tour de France

Jacques Anquetil and Raymond Poulidor #cyclinglife #cyclelife #cyclingvideos #cyclistsofinstagram #cyclingpics #cyclists #cyclingstyle #cyclingphotos #cyclistlifestyle @sarpergunsal @berkemceylan @seytanarabasi @canereler pic.twitter.com/HlAkXkh7Eo— Gökhan Derin (@cyclist_merch) August 14, 2019

But for anyone in their 30s or younger, the Puy de Dôme represents a mothballed snapshot of a bygone era of professional cycling and the Tour de France, a romanticised moment (imagined or otherwise) of the sport captured in time, before EPO, Lance, and the Sky train.

It has played host to some of the sport’s most symbolic, transcendental moments, from Fausto Coppi’s win on the climb’s debut in 1952 to Bernard Hinault’s first stamp of authority on the Tour in 1978 (and, incidentally, the Badger’s final concession to teammate and heir apparent Greg LeMond in 1986).

The Puy was also the scene of the beginning of the end of one of cycling’s defining eras. In 1975, Eddy Merckx, aiming for his sixth Tour win and momentarily succeeding in keeping Lucien Van Impe and home favourite Bernard Thévenet within arm’s reach on the summit finish, was punched in the kidneys by spectator Nello Breton. Injured from the impact of Breton’s ‘accidental’ intervention, the Cannibal’s reign at the top of his sport would end in Pra-Loup two days later.

Eddy Merckx & Joop Zoetemelk dans le Puy de Dome (Tour 1975). Dans quelques km un imbécile va frapper le champion belge...

📸 MC#EddyMerckx #Zoetemelk #PuydeDome #TDF #TDF1975 #TDF2023 #cycling pic.twitter.com/Iw0nVjAOoi

— Miroir du Cyclisme 🇺🇦 (@Miroir2Cyclisme) October 4, 2022

However, there is one day, one image, and two racers, that encapsulate the Puy de Dôme’s lofty standing in Tour lore more than any others. In 1964 Maître Jacques Anquetil was four Tours to the good, an imperious, undroppable, but not extremely popular presence at his home race. Meanwhile, the younger Raymond Poulidor, who finished third overall two years before, had emerged as his closest rival for the yellow jersey, and the true owner of the French public’s affections.

By the final mountain stage of the 1964 race, to the summit of the Puy, the two Frenchmen – representing to fans the polar extremes of a cyclist’s character: one a relentless winning machine, the other a charismatic underdog – were separated by only 56 seconds on the GC.

While Julio Jiménez and Federico Bahamontès tore off up the ever-steepening road to the top of the volcano, the stage win and mountain points in mind, Poulidor and Anquetil remained locked together behind, literally shoulder to shoulder, matching each other pedal stroke for pedal stroke.

Was Anquetil bluffing, riding alongside his rival in an attempt to conceal his discomfort and to dissuade the overly cautious Poulidor from attacking? We’ll never know, but when Poulidor finally unleashed his killer blow – within sight of the summit – he managed to put 42 seconds into the battling, for once ragged Anquetil in under a kilometre.

Despite the pyrotechnics, it was all too little, too late: the defending champion remained in yellow – by 14 seconds. “That’s 13 more than I need,” he said at the finish. As Maître Jacques slumped exhausted onto the bonnet of his team manager’s car at the top of the volcano, the myth of Anquetil and Poulidor’s rivalry – and of the Puy de Dôme – was born.

The black and white photo of Anquetil and Poulidor going shoulder to shoulder on the Puy de Dome in 1964 is one of cycling’s most treasured images, but here they are, in colour, on that same climb. PouPou’s shoulders are the closest he’d get to wearing yellow on the Tour. pic.twitter.com/alPZlPCqLu

— Felix Lowe (@saddleblaze) November 14, 2019

However, all good things must come to an end, for three and a half decades anyway. By the late 1980s, the continued expansion of the Tour into a global behemoth, with its cavalcade of vehicles and infrastructure, had made hosting the race on the Puy de Dôme a logistical nightmare, a difficulty only enhanced by the construction of a rail line to the summit in 2012, further shrinking the already narrow road.

While it was still used by adventure races such as the Transcontinental, where it hosted the 2017 edition’s first checkpoints, the Puy’s days as a Tour summit finish were thought to be long gone.

But now, as Christian Prudhomme told us this morning, after 35 long years, it’s finally back at the Tour. So what should we expect next summer?

Well, first of all, don’t be expecting Mathieu van der Poel to emulate his grandfather on the volcano’s fearsome slopes (though you never know with MVDP). Because the Puy de Dôme is a relentless monster of a climb.

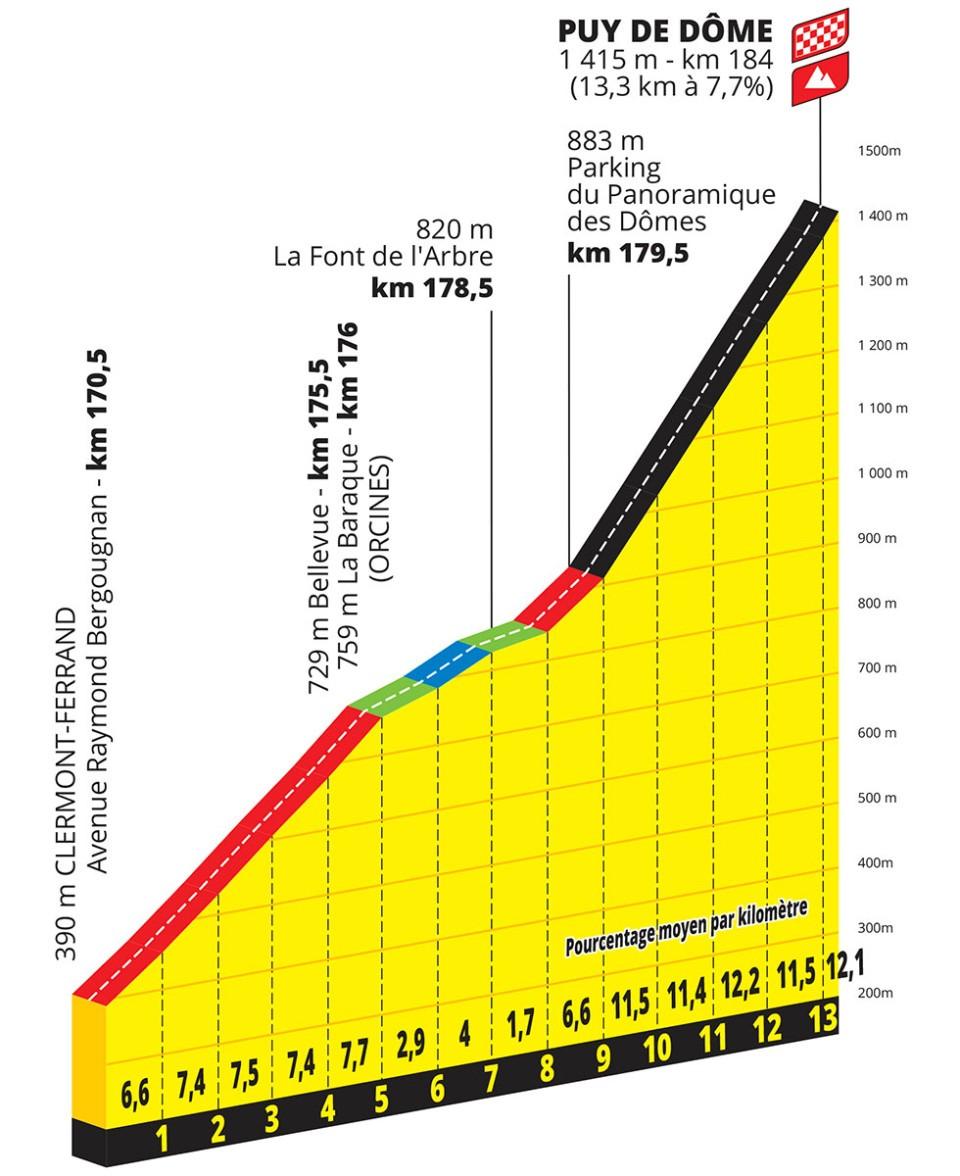

Rising sharply enough out of Clermont-Ferrand – which will help whittle down the peloton before the road steepens and narrows towards the summit – the road then eases off for three kilometres of relative false flat before stage nine’s defining moment on the dome.

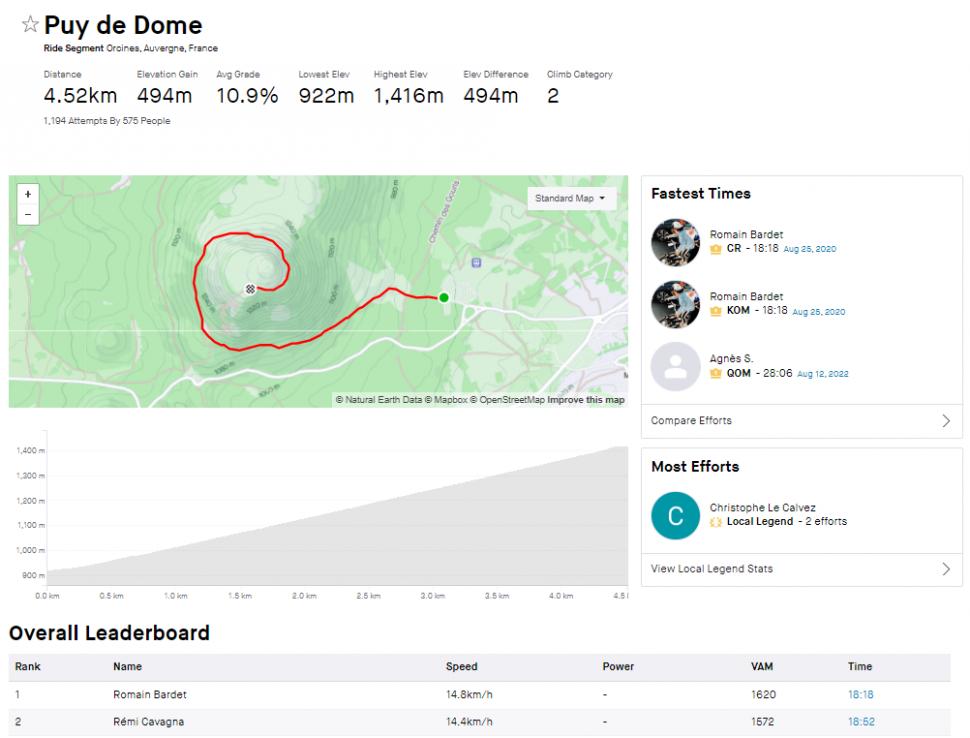

The final four kilometres are, it’s safe to say, savage. According to VeloViewer, the unrelenting gradient never dips below 11.5 percent, and touches 16 percent in places. It may not be the longest climb, but it will certainly do some damage, and will likely favour a climber capable of withstanding steep gradients while retaining some sort of kick at the end. A Tadej Pogačar then, or perhaps a home victory for Romain Bardet (the current Strava KOM)?

Regardless of who comes out on top next summer, by saving the Puy de Dôme from extinction, Tour organisers ASO have once again succeeded in marrying innovation with the race’s storied past.

The 2023 Tour routes

So, what’s happening with the rest of next year’s Tour routes?

Well, the men’s race is a bit of an odd one, to say the least. It’s certainly not what could be described as a Tour of France, missing as it does great swathes of the south-east and basically the entire north of the country.

The condensed nature of the route, focusing heavily on the Pyrenees, Massif Central and the northern Alps, notably means that there is only one lengthy 500km transfer – take note, Giro organisers – from the penultimate, potentially decisive stage to Le Markstein (the scene of Annemiek van Vleuten’s devastating long-range attack to take her first yellow jersey last year) to Paris.

A hilly start in the Basque Country – the Tour’s second foreign Grand Départ in as many years – lends itself to an opening week resembling that of the 1992 Tour, which also began down the road from Bilbao in San Sebastián. The Tour’s southern opening, like in 1992, necessitates an early and relatively benign two-day spell in the Pyrenees before the race’s second weekend (though I’m not sure the riders would agree with me describing a stage featuring the Tourmalet as ‘benign’). A lumpy weekend in the Massif Central, culminating in the aforementioned Puy, will then take the riders into the first rest day.

A varied week two features a few opportunities for the puncheurs and sprinters before a trio of Alpine delights, including summit finishes at the Grand Colombier (on Bastille Day) and Saint-Gervais, while the dreadfully steep Joux Plane acts as the focal point of stage 14 – and next year’s Étape du Tour – before the fast, hairy plunge into Morzine. Have fun, if you're planning on riding that!

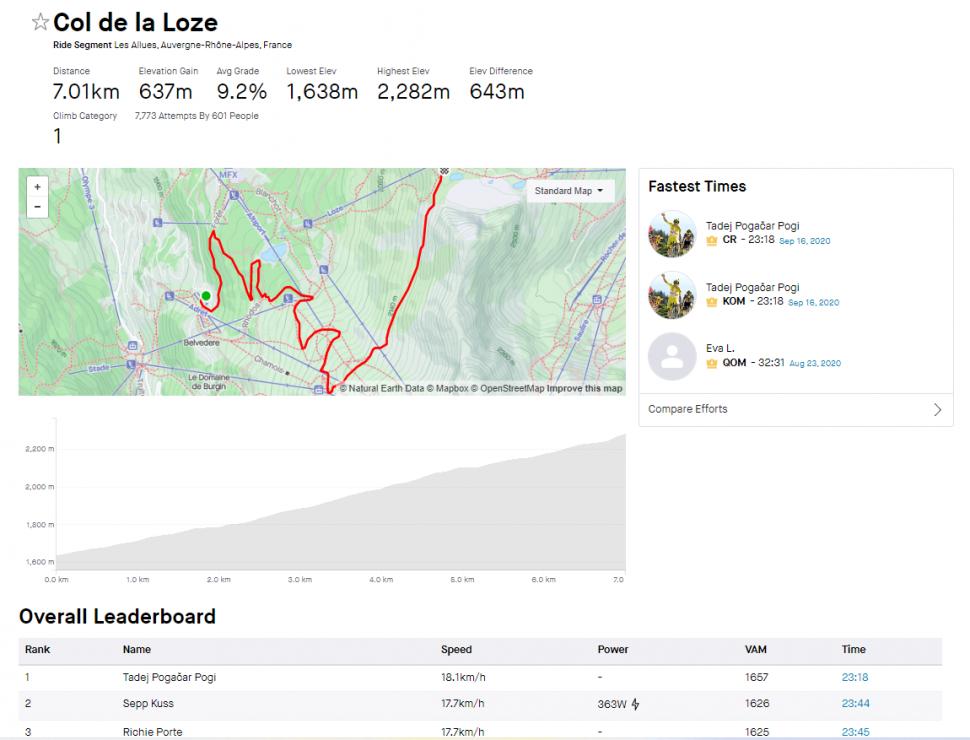

The final week kicks off with the only time trial of the race, a hilly 22km affair featuring the Côte de Domancy, where Bernard Hinault stormed to the rainbow jersey in 1980. The 2023 Tour is certainly not kind to the time triallists – only 2015 had fewer individual time trialling kilometres in the post-war period, and even it had a team effort – an observation underlined by the following stage’s inclusion of the Col de la Loze, the roof of the race and the scene of Tadej Pogačar’s brief wobble in 2020.

The route is, however, more favourable to the sprinters (for once). There are nine potential stages for the fast men, an apparent reversal of ASO’s anti-bunch kick bias in recent years. Two final-week flat transition stages (a rarity in the modern Tour) will take the riders to the Vosges for what the organisers will hope is a decisive, suspense-filled penultimate day.

> No Country for Fast Men: Why is this year’s Tour de France so unkind to sprinters?

Meanwhile, suspense will almost certainly be the name of the game in next summer’s Tour de France Femmes, the second edition of the revamped women’s race.

While last year’s race stuck to the north of the country, the 2023 route ventures south for what should be a thrilling final weekend in the Pyrenees. After providing base camp for the men as they tackle the Puy de Dôme two weeks earlier, Clermont-Ferrand will again play a starring role in the Tour Femmes, kicking the eight-day race off with a flat opening stage that Lorena Wiebes will surely have marked in her calendar.

ASO/Fabien Boukla

The second stage to Mauriac is a grippy introduction to the hills, while the final ramp to the line will provide an early GC shakeup. Another sprinters’ stage to Montignac-Lascaux will precede a biting, hilly finale into Rodez, tailor made for the puncheurs. Rodez will also offer the final opportunity for the less-than-confident climbers (i.e. anyone but Annemiek van Vleuten) to take time before the Pyrenees, as two flat stages to Albi and Blagnac transport the peloton south into the mountains.

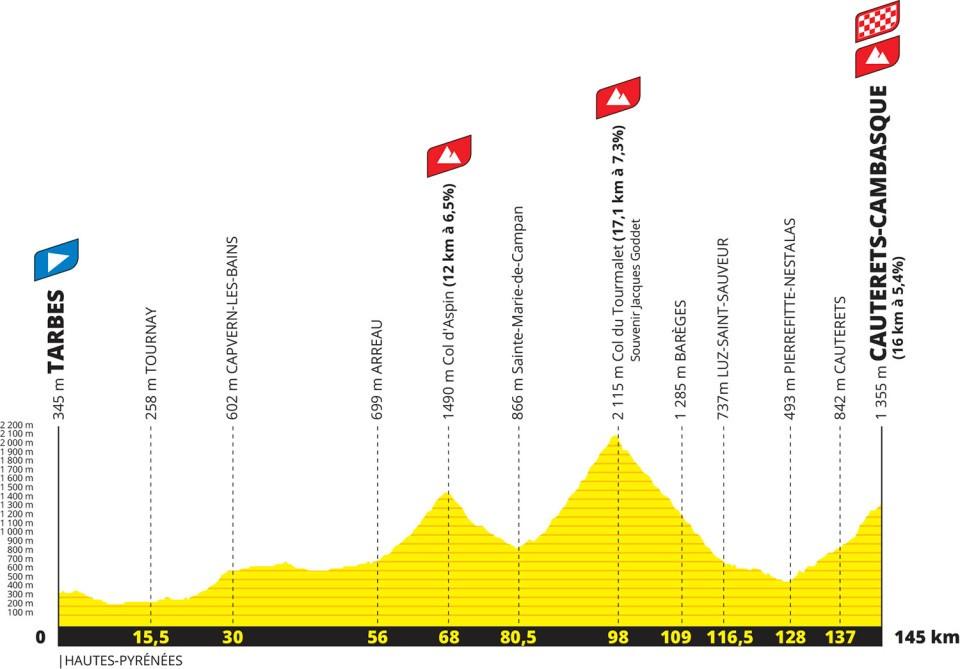

Stage seven of the 2023 Tour de France Femmes may only be 90 kilometres long, but it’s a classic Tour stage. The Col d’Aspin, first tackled in the men’s race in 1910, acts as the amuse-bouche (well, a 12 kilometre amuse-bouche, anyway) before the peloton ascends to the summit of one of the Tour’s iconic climbs, the 17km-long, 7.3 percent Col du Tourmalet. Expect fireworks – probably from a Dutchwoman in a Movistar jersey – on what will surely be a defining day for the race, and a symbolic moment for the women’s side of the sport too.

If Van Vleuten hasn’t blown the race apart on the Tourmalet, her rivals will have one more chance to usurp the defending champion during the final day’s 22km time trial in Pau. The gateway to the Pyrenees has hosted the men’s race 74 times (third in the all-time list behind Paris and Bordeaux), and will provide a fitting conclusion to four weeks of top-tier racing.

Let’s just hope we’re treated to a suspense-filled final day against the clock, and not any of the other, more murky goings-on associated with the men’s sojourns in Pau down the years…

After obtaining a PhD, lecturing, and hosting a history podcast at Queen’s University Belfast, Ryan joined road.cc in December 2021 and since then has kept the site’s readers and listeners informed and enthralled (well at least occasionally) on news, the live blog, and the road.cc Podcast. After boarding a wrong bus at the world championships and ruining a good pair of jeans at the cyclocross, he now serves as road.cc’s senior news writer. Before his foray into cycling journalism, he wallowed in the equally pitiless world of academia, where he wrote a book about Victorian politics and droned on about cycling and bikes to classes of bored students (while taking every chance he could get to talk about cycling in print or on the radio). He can be found riding his bike very slowly around the narrow, scenic country lanes of Co. Down.

Latest Comments

- Bungle_52 4 sec ago

That one was completely different though, it was a driver not a car as in the other 3. So 1 in 4 of the stories manage to follow reporting guidelines.

- Rendel Harris 1 hour 52 min ago

Absolutely they could have. Tarmac is a petroleum-based product and its surface can be very oily when it's newly laid. This is particularly the...

- ROOTminus1 7 hours 54 min ago

I'm glad the article went into more detail and cleared things up, the headline had me worried that some autonomous building had run rampant and...

- mark1a 8 hours 13 min ago

Still here, just showing a few signs of wear and tear. Hopefully still serviceable for some years to come.

- Secret_squirrel 8 hours 43 min ago

Has he fully recovered though, and will he ever?...

- Rendel Harris 8 hours 57 min ago

How can you know that you are "equally fearful" as "any female cyclist"? There is no possible way of quantifying such emotions and female cyclists...

- chrisonabike 9 hours 29 min ago

I think it would be fairer to blame the moon - as in "my client is a loony".

- Bungle_52 9 hours 53 min ago

Nice idea but Gloucestershire Constabulary are not interested as exemplified by this prvious NMOTD. Not only was there NFA for the close pass in...

- hawkinspeter 11 hours 24 min ago

I think black boxes are great for early detection of cognitive decline and/or sight problems. Someone's driving is going to become much less smooth...

Add new comment

5 comments

Again, as I said when the Giro route was announced, I don't understand why the Giro is getting it in the neck so much about this. OK, their final day transfer is 700km rather than 500km, but otherwise the transfers look about the same. Last year the Tour did the massive transfer from Denmark to France and I don't recall anyone mentioning its environmental impact, why has the Giro suddenly become the whipping boy for something all the GTs do?

Very excited about this. I rode up it in 2019 and the last 4.5km are steep. Ever since, I have hoped that it might make a return to the Tour one day.

Did you get in on the lottery? I applied for a couple of years but without luck, would love to have had a crack at it.

Yes - 2019 I think it was. Really pleased to have done it. The Auvergne, including the Cantal further south offers some fantastic climbs. Puy Mary is my other favourite.

I'm going to get there one of these years, hopefully some climbing combined with watching Clermont Auvergne play rugby.