- News

- Reviews

- Bikes

- Components

- Bar tape & grips

- Bottom brackets

- Brake & gear cables

- Brake & STI levers

- Brake pads & spares

- Brakes

- Cassettes & freewheels

- Chains

- Chainsets & chainrings

- Derailleurs - front

- Derailleurs - rear

- Forks

- Gear levers & shifters

- Groupsets

- Handlebars & extensions

- Headsets

- Hubs

- Inner tubes

- Pedals

- Quick releases & skewers

- Saddles

- Seatposts

- Stems

- Wheels

- Tyres

- Tubeless valves

- Accessories

- Accessories - misc

- Computer mounts

- Bags

- Bar ends

- Bike bags & cases

- Bottle cages

- Bottles

- Cameras

- Car racks

- Child seats

- Computers

- Glasses

- GPS units

- Helmets

- Lights - front

- Lights - rear

- Lights - sets

- Locks

- Mirrors

- Mudguards

- Racks

- Pumps & CO2 inflators

- Puncture kits

- Reflectives

- Smart watches

- Stands and racks

- Trailers

- Clothing

- Health, fitness and nutrition

- Tools and workshop

- Miscellaneous

- Buyers Guides

- Features

- Forum

- Recommends

- Podcast

feature

Frame Meisters

Drive down a nondescript road in a small nondescript town somewhere between Bruges and Ghent and turn down an incongruous driveway between two nondescript but decidedly Belgian houses, go past the collection of outdoor barbeque sets on the right and you’ll find yourself looking through a double window at some wonderful examples of work from one of the longest running and most historic bike manufacturers that you’ve never heard of. Dribbling a little.

Step inside and there’s the crisp clean showroom you’d expect from the bespoked bike trade nowadays with an open plan workshop in the back and via a full width window in the rear wall the vast framebuilding area is visible. Various bikes are on display, all touchy-feely, look at that frame detail, stroke that paint job, spot another nice bit. Hmmm, nice things. I’m handed a Jupiler beer, got to conform to the Belgian stereotype, and to the crack-hiss of a fingered ring-pull Steven from Jaegher and I start to talk about bicycles.

Jaegher bikes have been going for four generations, or since 1934 if you prefer that timeline, a heritage most other bike brands would be justifiably proud of and make a big fuss over. The business was started by Odiel Vaneenooghe, a bike racer who was good enough to win a stage of the Tour of Belgium, and it’s been handed down via Etienne to the current builders Luc and great-grandson Diel. It all began when Odiel started to build frames for the simply practical reason that he couldn’t find a good enough frame locally, needing to travel to Brussels or further afield to get one, so he started to make them himself. As you do. And as is often the way other riders asked him to build frames for them which in turn led to Odiel setting up his own bike shop combined with a pub, which was quite a common thing in those days, it’s not just some modern tattooed bearded hipster invention. Son Etienne followed in his footsteps and from there on things got bigger and better; with frame building reaching its height in the 1960’s and 70’s when the Jaegher shop had a staff of almost 30 and knocked out 100,000 frames a year, all with other people’s names stickered on them for a variety of Dutch, Belgian and German brands.

The majority of those frames were basic workaday steel bones for standard unglamourous blue-collar bicycles; utility bikes, postman bikes, that sort of thing, but they also did a line in top end race frames, also without the Jaegher name on the downtube. Back in the day It was common practice for a Pro rider’s frame to be made by someone other than who was mentioned on the downtube as one steel bike looked pretty much like another, and for a period of six years Jaegher made all the frames for the Molteni team, which included a certain Eddy Merckx on the roster, you may have heard of him. This is something many other bike builders might be making a big noise about, splashing it all over their websites and brochures, and maybe putting a sticker on their frames, it’s a heritage and history that some marketing men can only dream of, and yet Jaegher are almost being almost coy about it. Steven mentions that Sean Kelly also rode one of their frames, as well as about half of the Belgian Pro peloton at the time, muttered almost as an aside. Quiet pride I think.

That kind of racing heritage continues with one of their bikes winning the TransContinental race in 2014. That’s London to Istanbul, and a distance of 3400km in 7 days 23 hours under the legs of Kristof Allegaert. On a steel bike and not some carbon piece of ubertech. That probably passed you by as well.

The Jaegher name made it onto the downtube in it’s own right and became it’s own brand towards the end of the noughties, the family were bored of working to other people’s constraints and were keen to build to their own standards, and those standards led them to constructing only top end steel frames without any compromise to tube quality or paint finish. They sniffed that something was in the air; the wafts of the resurgence of the steel frame after the dominance of alloy and carbon, and the recent advances in steel tube technology that meant a ferrous bike could be built that had the potential to be both relevant and competitive in the current market.

Jaegher build mostly with Columbus tubing, and of that principally from the top-end Spirit and XCR tubesets, they might throw a little bit of Reynolds into the mix if it warrants it as each frame is custom built to suit each individual customer. Current frame production is at 100 - 150 per year with about a three month wait time as it’s just the third and fourth generations of the Jaegher cycling family working out the back of the shop. Father Luc does the lug work of the Phantom and the Crusader whilst son Diel does the TIG welding on the Interceptor, Ascender and Mirage frames.

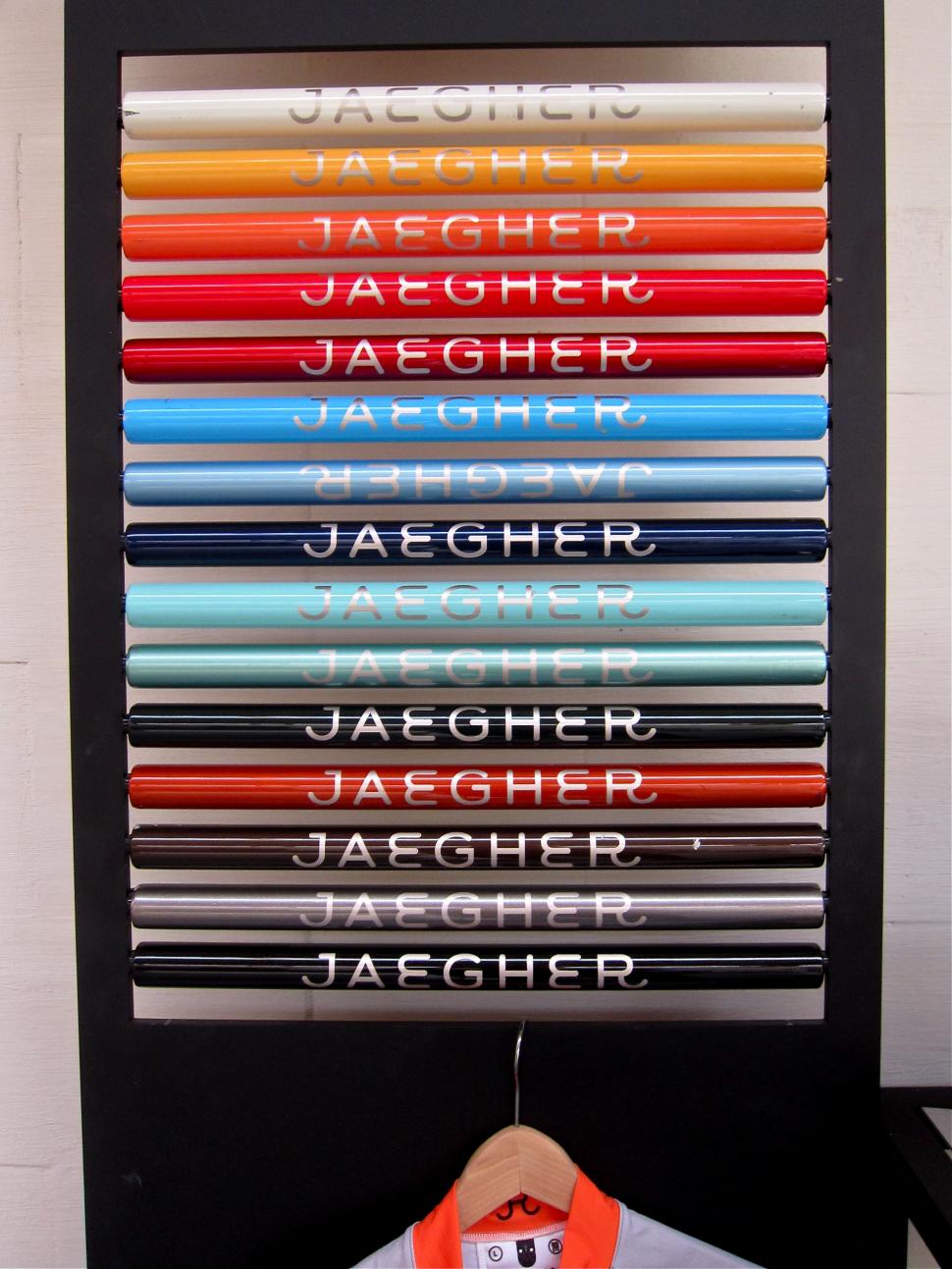

Once that’s done the frames are taken a few streets down the road where they’re painted by David Meirhaeghe, brother of Filip Meirhaeghe, four times Mountain Bike World Champion and Olympic medal winner. More cycling heritage anyone? They might have to wait a bit as the sprayer may be busy on a Pros bike; it’s where all the custom paint work for Cavendish, Contador, Nibali, Sagan, Kwiatkowski, Stybar and a whole lot more of the peloton gets done. As a frequent first point of introduction to a bike brand in today’s backlit screen dependent world the paint jobs on the Jaeghers are definitely podium quality, thick and deep enough to entice you in further.

If a Jaegher frame tickles your fancies then they can build a bike to your own measurements, give you a bikefit (they have a strong relationship with the Bakala Academy, the main bike-fitter in Belgium), or mix the two up and make subtle changes to a bike you already own. Standard bike builder fare really. Each of the Jaegher models can be adapted for track or cyclo-cross or disc, tweaked to accept on-trend wider tyres, bosses for racks added, all the sorts of things you’d expect a quality framebuilder to offer as options. They’re happy for you to turn up with your own ideas and accommodate them on your new bike frame, but they’re not afraid to tell you if what you want might possibly be wrong.

Jaegher don’t have a rack of stock frame sizes you can pick up off the rack if you’re pretty normally shaped and just want a frame, despite that system making things quicker and easier for their frame production they’d rather tailor each frame to fit each rider. For example if you’re a bit taller than usual, a bit more powerful, or carrying a bit of timber, then you might benefit from the SuperStiff variant of the Interceptor. Jaegher subscribe to the idea that fit and comfort are far far bigger factors to optimizing pedaling performance than the ubiquitous quest of shaving weight or adding aero, but nevertheless they try and keep their frames as light as possible. Each frame they build embodies a constant search for tiny incremental improvements, and they’re in continual conversation with tubing manufacturers to advance tubing technology and get tubes drawn to their own spec.

While Jaegher has a varied customer base the majority of the riders are of the more mature end of the spectrum, but that’s mainly down to having the budget to afford a custom bicycle frame, with most of the framesets hovering around the mid €2,000, and with the range topping out at €3.5K you’re going to need a long paper-round if you’re a teenager to afford one. Like a lot of custom framebuilders they’re seeing a wave of customers come back to steel after doing the rounds of alloy and carbon-fibre bikes, riders that feel they need something made-to-measure, something different and a bicycle that appeals to their aesthetic sensibilities more. Jaegher are also increasingly experiencing clients that are buying bikes on ecological grounds; something that is made locally and not transported from halfway round the world, made by a person they can actually talk to. And steel tends to be a bit more easily recyclable than carbon-fibre.

Step out the back and it’s exactly like you want a frame-builders to be, the fine mixture of grubby and industrious mixed in with a fair dollop of craft. The space behind the Jaegher showroom is vast when compared to most other frame-builders areas and a wonderful place to wander around and just look at things. Lugs, tubes, tools, drawings, machinery. Things. The stations where the welding and brazing are done, frames mid way through production and some antiquated and vast machines out the back from the mass-production days.

The trouble with going to any framebuilders and talking to them about their expertise, talent and art, their loves and reasons, looking at their process and fondling the bike bits they master into frames is that by doing so you’re making a strong tactile emotional connection or two and you pretty much end up wanting to buy one of their frames before walking out the door. Never share a beer with them, that makes it even worse. And there is that Jaegher on a stand over there that’s just my size and more importantly, just my colour. Luckily for the meantime at least I can bypass that expensive and vulgar mentioning of money as I’m lent a Campagnolo Record 11-speed equipped Interceptor frame to try for a couple of days, which is handy. A bike in my size is wheeled out and allen keys are readied to set the saddle to the right height and pitch, I give them my measurement and the saddle is already at exactly that height. Some would see it as a sign.

If you can get off a bike that you’ve never ridden before after two days of riding, one of which is smashing out near on 100 miles, large sections of which were on some of the most infamous sections of Belgian cobble and can still make it to the evening meal without walking like you’ve got a barrel of Leffe between your legs and a back that wants to fold in on itself like a cheap patio chair then I class that as a pretty hearty commendation of a good bike. That’s not to be taken to constitute a proper review though, more of an impression.

The Interceptor will appeal to those who like their bike to look like a bicycle; straight tubes, triangles, not something left against a radiator to go a bit soft. The black with a glitter clearcoat frame here with the discreet accents of colour and all black Campag groupset gives this Interceptor an air of understated charm and efficient business. You can change that colour to best suit your character though.

Made from Columbus Spirit tubing the Interceptor is a comfortable ride, if anything’s going to test a bike’s metal mettle then it’s going to be the cobbles of Belgium, and while there was enough holding on and teeth gritting required to survive the frame did a noticeable job of shaving the edge off the clatter and bounce. Compliant is a clichéd word to use in bike reviews and thankfully the Jaegher doesn’t quite warrant that disservice, ‘supple’ would be a far better description of the ride. Which I prefer in a bike to be honest.

There’s a certain spring in the frame, which is another steel frame cliché, I'm sorry, it’s firm under powered pedaling rather than stiff, so if you’re a sprinter or a masher then the Interceptor S-Stiff variant would be worth a look. It’s also not a climber’s bike either, although it could never be classified as heavy it doesn’t have the svelte snap of a gossamer frame. But what the Interceptor is just happens to be a fantastic all-day bike for a bit of everything, you know, the sort of riding that most of us do most of the time. It’ll go fast if you want it to, it’ll cruise along quite happily as well, and it’s comfortable enough for those long hours on the road. Put simply it's a nice bike to ride.

Drive down a nondescript road in a small nondescript town somewhere in Belgium and turn down an incongruous driveway between two nondescript houses, go past the collection of outdoor barbeque sets and you’ll find something rather special.

Jo Burt has spent the majority of his life riding bikes, drawing bikes and writing about bikes. When he's not scribbling pictures for the whole gamut of cycling media he writes words about them for road.cc and when he's not doing either of those he's pedaling. Then in whatever spare minutes there are in between he's agonizing over getting his socks, cycling cap and bar-tape to coordinate just so. And is quietly disappointed that yours don't He rides and races road bikes a bit, cyclo-cross bikes a lot and mountainbikes a fair bit too. Would rather be up a mountain.

Since we're talking (checks thread again) why UK cycle sales have plummeted to 1970s levels, and now "infra" and "US" ... surely one of the best...

I thought that too, but apparently you can get safety compliant bull bars. I'm sure they're safe relative to the ones that became popular in the...

Driver hospitalised after flipping car onto roof in Swindon street...

Granted, given the width they didn't manage to quite block all the cycling access, but they tried...(from here - skip to the other side to see the ...

I agree, TV coverage of three stages as a one-time-only does nothing for the sport of cycling.

One of, and maybe the only, redeeming value of the post-my-life culture, is that some of the adherents will do the cops' job for them -- which is...

You can both be right - the scheme was introduced by Labour, but the fines levied under it increased dramatically in 2023 under the Tories.

Agreed, there was no supension. There were various modifications of the plan, and a long time before the Beafort Rd and Crews Hole Rd one way plan...

My only use for a camera is for "evidence". I only check it (& check before and after every ride) to make sure it is working. While I have had...

I don't see anything in what they said to suggest that they even think about 3rd party reporting of dangerous driving as being part of the picture...